Evidence of Black Africans in the Bible, by Dan Rogers

In 1992, I took a class at Emory University in Atlanta called Introduction to the Old Testament. As I read the various required textbooks for the course, I saw something I had not noticed before. Many Old Testament scholars, particularly European scholars of the 18th, 19th and early 20th century, had written their books and commentaries on the Old Testament from the perspective that there were no people of color mentioned in the Scriptures.

|

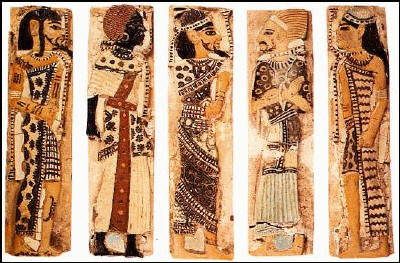

Different nationalities depicted in tomb of Ramses III: |

Puzzled, I began to look into the topic more deeply. I studied intensively for about a year, attending lectures and interviewing scholars. I began to realize that this was a particularly difficult and controversial subject, and it has caused much hurt. Thankfully, times have changed, but some of the wounds remain. So let’s look at it, and put to rest once and for all this biased and unfair distortion of the Bible.

Let me apologize in advance for some of the terms that I will need to use as we discuss this topic. They are not the terms we would prefer today, but they are terms that historians, ethnologists and Bible commentators of past centuries, and even the 20th century, have employed to explain their ideas about the origin of blacks. These ideas, steeped in racial prejudice, were alleged to provide a biblical justification for black slavery and the subjugation of black peoples.

When I first read about these concepts, they brought tears to my eyes. As a white person in a predominantly white country, I also began to gain a better understanding of and a greater appreciation for the black experience in the United States.

Is the Bible a book by a white God for white people? Of course not. God is spirit and does not have “color” in our human and earthly sense. There is nothing in the Scriptures to indicate that people are excluded from God’s saving grace on the basis of ethnic origin or skin color. God is “not wanting anyone to perish” (2 Peter 3:9). Jesus is the Savior of all peoples. Nevertheless, it is a fact that the majority of European artists and Bible commentators painted and described all biblical characters, including God, as white. This had the effect of excluding blacks from being a part of Scripture and has led some people of color to question the Bible’s relevance to them.

Exclusion was only one side of the problem. Where the presence of blacks in the Bible was admitted, primarily among uneducated whites, outrageous myths and fables abounded. This was especially true among white Christians living in the southeastern United States prior to the Civil War. These denigrating tales were believed to support the racist (and unbiblical) notion that the Bible supported a white subjugation of black people.

What do we mean by “black”?

There are several difficulties surrounding any discussion of this sensitive topic. Some are obvious; others are less so. Not least is the question, what do we mean by “black” people? In America today, we mean African- Americans—those with African ancestry and dark skin color. But is that how the people who lived when the books of the Bible were written would have thought?

There are differences between ancient and modern concepts of what “black” means when it is applied to people. For example, in the table of nations in Genesis 10, the word used to describe the people descended from Ham in the ancient Hebrew, Akkadian and Sumerian languages is related to the color black. But what does this mean? Our traditional understanding of the Old Testament is influenced by the ancient rabbinic method of interpretation known as Midrash. These interpretations sometimes take precedence over the literal meaning of the text being interpreted. They also belong to another time with other socio-economic conditions and concerns. When ancient rabbinic literature mentions black people, does it mean ethnically “Negro” or just people of generally darker skin?

Let me give you a modern example. In a congregation I once pastored were two families with the surnames Black and White. The Whites were black and the Blacks were white. Mr. Black, who was white, used to talk about his lovely white grandchildren who were Blacks. And Mr. White talked about his lovely black grandchildren who were Whites. Imagine what someone a thousand years from now would think if they read that.

Just because some people are called by a term meaning “black” does not necessarily prove they were what we now call black. Of course, it does not mean that they were not “people of color” either. In ancient times, just as folks did in the old frontier societies of our country, people often were given names that reflected their personality, where they were from or their appearance. But names like “Slim,” “Tex,” “Kid,” “Smitty” or “Buffalo” tell you nothing of a person’s ancestry.

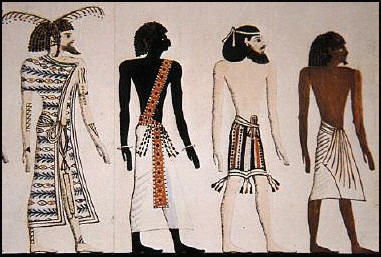

Some ancient writers say that the Egyptians and Ethiopians were black. But what do they mean? How “black” were they? Were they merely darker than those doing the writing? The wall paintings and hieroglyphics of the ancient Egyptians and Ethiopians picture some people as black in color. But this was a highly stylized art form, and may have nothing to do with their actual skin color.

Some black people are much fairer in skin color than some we classify as “Caucasians.” There are also social and legal definitions, based on the percentage of African or “Negro” blood people have in their ancestry. It was not so long ago that certain states had laws that stated that someone was a “Negro” if the person had even a single black ancestor. Physical appearance did not matter.

These are some of the difficulties of trying to determine if people in the Bible are what today we consider black. It is therefore irresponsible to draw superficial conclusions either for or against a black presence in the Scriptures. But this did not stop scholars and theologians (who surely should have known better) from suggesting that all people in the Bible were white, and that the Bible record excludes the Asian and “Negro” races, a conclusion that is not true.

But suppose it were true? What difference would that make? The Bible account focuses on what we now call the Middle East, and in particular the rags-to-riches-to-ruin story of ancient Israel. It is specific to geography and to a historical period. Other people are mentioned as they pertain to the unfolding of that story. So Eskimos (or Inuit) are not included, nor are Koreans. Yet no one seriously believes that they are excluded from the human race. But when it comes to the alleged absence of black people, we encounter a web of cruel deceit that makes a mockery of the true biblical record. Only when you understand this can you begin to get a glimmer of what it has been like to be black in America.

Several views

Among those who have accepted the presence of black people in the Bible, several different views as to the origin of blacks were postulated. Let’s look at some of these.

The pre-Adamite view argues that blacks, particularly so-called “Negroes,” are not descended from Adam. This view appears to have its origin in the works of such authors as Paracelsus in 1520, Bruno in 1591, Vanini in 1619 and one of the most prolific writers, Peyrère, in 1655. It reached a high level of development with the 19th-century scholar Alexander Winchell in his book, Preadamites; or a Demonstration of the Existence of Men Before Adam, published in 1880.

These writers (all of them white), argued that blacks belong to a race created before Adam and from among whom the biblical villain Cain found his wife. Cain, by marrying one of these pre-Adamic peoples, the reasoning goes, became the progenitor of all black people. Therefore, it was rationalized, black people, especially “Negroes,” are not actually human, because they did not descend from Adam but from some pre-Adamic creation, having entered the human race only by intermarriage, and that with a notorious sinner. As non-humans, therefore, they did not have souls, but were merely beasts like any other beast of the field. And since the Bible says God gave humans dominion over the beasts, it was concluded that these soulless creatures exist to do work for the humans.

This preposterous theological premise was preached in churches across the United States, particularly in the Southeast, to reassure people that slavery was not only acceptable, but the very will of God, rooted firmly in a “proper” understanding of the Bible.

The Cainite view argues that Cain was born white, but after his unacceptable sacrifice and the murder of his brother, Abel, he was turned black as punishment and became the progenitor of all black people. According to some of the rabbinic Midrashim (in both the Babylonian and Jerusalem Talmud), because Cain offered an unacceptable sacrifice, the smoke from this unacceptable sacrifice blew back on him, turned him black and caused all of his children to be born black. In another Talmudic story, a rabbi says that God beat Cain with hail until he turned black. Stories vary, but it became a common Euro-American belief that God cursed and marked Cain by turning him black.1

The Noahite (or old Hamite) view can be traced to writings suggested in the Talmud and later adopted by Jewish and Christian interpreters (especially among white southerners in the pre-Civil War United States). In this view, Ham violated God’s supposed prohibition against mating on the ark. Because he could not resist, he was turned black. Yet another teaching was that Ham and/or Canaan were turned black as a result of Noah’s curse in Genesis 9:24-27. In this view, because God cursed Canaan, that curse was to go on all of Canaan’s descendants and the curse was, first, that they would all be turned black, and second, that they would be servants to white people. Again, we see here a blatant attempt to interpret the Bible in a way that justifies the institution of black slavery.

The New Hamite view is a 19th-century view that holds that Hamites were all white rather than black with the possible exception of Cush. (Cush is a Hebrew term that means “black one.”) Scholars, particularly in 19thcentury Germany, said that even if Cush were black in color, he must be regarded as a Caucasoid black. Why? Because, in their view, Negroes were not within the purview of the writers of the Bible. Even some modern biblical scholars hold this view. For example, Martin Noth, considered to be one of the most respected Old Testament scholars of all time, states on page 263 of his book The Old Testament World (Fortress, 1966) that the biblical writers knew nothing of any Negro people.

Understandably, there has been a reaction among black theologians and black people to these ideas. Some have tended toward the opposite extreme, arguing that everyone in the Bible was black. Dr. Charles B. Copher, professor of African American Studies at Interdenominational Theological School in Atlanta, says this view is patently outlandish. He believes that this notion is an overreaction that can lead to another kind of extremism.

The Adamite view. The Adamite view is the orthodox Jewish, Christian and Islamic view. It is based (for Christians) on Acts 17:26, which states that God made all people from one original bloodline, or one source. This, we emphasize, is the only view that is consistent with the true message of Scripture. Nevertheless, these other hideously distorted ideas have been promulgated, and some still have a degree of influence even today.

So what?

So, where does that leave us? Feeling slightly nauseated, I hope, over the amazing ability we have to delude ourselves and bend the word of God in any direction that suits our purposes.

The overall and surely indisputable message is that God has created us all in his image and has included all members of the human race in the saving work of his Son. Nowhere does the Bible give any indications that black people, or any people, whether “of color” or not, are outside the embrace of his love. But the fact remains that people have believed and taught this error, and sadly, it has been a teaching that still affects the way many of us think about each other, and perhaps even ourselves. The Bible does not focus on skin color as any form of criterion. All have sinned, all have fallen short of the glory of God, and all are recipients of his grace through Jesus Christ.

But what about the question of whether black people are mentioned in the Bible? Admittedly it is difficult to build a definitive case, based on textual evidence, to prove beyond all doubt that black people are mentioned in its pages. But why should we have to? Let’s turn the question around. There is no evidence whatsoever that black people—or any people for that matter—are excluded from the purview of the writers of the Bible. Let us put the burden of proof on those who would teach otherwise.

Evidence in the Bible

The stories of the Bible took place in and around what we now call the Middle East, and people moved on and off its stage based on their relationship with the nations of ancient Israel and Judah. Consequently the vast majority of the world’s ethnic and racial groups are not specifically identified. But some of those who are identified were black.

|

From the tomb of Seti I: Syrian, Nubian, Libyan, Egyptian |

There is a strong tradition that some of the descendants of Noah through his son Ham were black. Ham had a son named Cush, which means “black” in Hebrew. Cush is the most common term designating color in reference to persons, people or lands used in the Bible. It’s used 58 times in the King James Version. The Greek and Latin word is Ethiopia. In classical literature, Greek and Roman authors describe Ethiopians as black. Archaeology has found these people to be black. In the book of Jeremiah, the question is asked, “Can the Ethiopian change his skin?”

Genesis 10:6-20 describes the descendants of Ham as being located in North Africa, Central Africa and in parts of southern Asia. Psalm 105:23 mentions the “land of Ham” in Egypt, and Psalm 78:51 connects the “tents of Ham” with Egypt.

Other Old Testament evidence

In Genesis 10, Nimrod, son of Cush (whose name means “black”), founded a civilization in Mesopotamia. In Genesis 11, Abraham was from Ur of the Chaldees, a land whose earliest inhabitants included blacks. The people of the region where Abraham came from can be proven historically and archaeologically to have been intermixed racially. So it is possible that Abraham and those who traveled with him could have been racially mixed.

Genesis 14 tells how Abraham’s experiences in Canaan and Egypt brought him and his family into areas inhabited by peoples who were very likely black. Both archaeological evidence and the account in 1 Chronicles 4 tell us that the land of Canaan was inhabited by the descendants of Ham.

Further black presence can be found in the accounts of Hagar the Egyptian, Ishmael and his Egyptian wife, and Ishmael’s sons, especially Kedar. The Kedarites are mentioned many times in Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel and Nehemiah, and the word kedar means “blackness.”

Still further evidence of black presence in the patriarchal period appears with Joseph’s experiences in Egypt. Joseph married an Egyptian woman, Asenath, who was descended from Mizraim, which made her Hamitic. Thus there is a strong possibility that Asenath was black. She was the mother of Ephraim and Manasseh.

The New Testament

The New Testament also contains ample evidence of a black presence. Acts 8 tells the story of the Ethiopian eunuch, one of the first Gentiles to be baptized. He came from a black region, so he may have been black. In Acts 13 we read of Simeon, called Niger, the Latin term for black. There is also Lucias from Cyrene, a geographical location of black people.

Do these references give us absolute proof? No. But the weight of evidence indicates that blacks were not excluded from “Bible action.” Modern scholarly opinion refutes the theologians who argued against a black presence in the Bible. But sadly, the past Euro-centrist interpretation of the Bible, which did recognize a black presence in the Bible, was deliberately used by some in the past to justify the subjugation and enslavement of peoples of color.

I believe it can be argued that there is a black presence in the Old and New Testaments. But either way, what is certain is that the Bible teaches that God has made all people of one ancestry. All humans—male, female, black, white, red, yellow and brown, are God’s children. They are all made in the image of God for salvation through Jesus Christ.

The New Testament makes it clear that no one is excluded from God’s love and purpose. Paul tells us that there is “neither Greek nor Jew, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Jesus Christ” (Galatians 3:26-29). God’s Word concerns, involves and speaks to all people inclusively.

We could sum it up in the words of the popular song:

Red and yellow, black and white, all are precious in his sight

Jesus loves the little children of the world.

Author’s note: This article is based on a paper I wrote while studying at Emory University in Atlanta. That paper was the product of much research, in the process of which I amassed a large bibliography, as shown below.

1 Some teach the opposite to be true, saying that God turned Cain white to make him easily recognizable (marked) in a Middle Eastern context. Some also teach that leprosy (in which the skin turned white) was the curse of God, thus white people are the real cursed ones. This view of Scripture, although equally distorted, nevertheless has had some influence in a disenfranchised black community.

Bibliography

Albright, William F. From the Stone Age to Christianity: Monotheism and the Historical Process. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1946.

______. The Old Testament World, George Arthur Buttrick (ed.) The Interpreter’s Bible. New York: Abingdon-Cokesbury Press, 1952.

______.Yahweh and the Gods of Canaan: A Historical Analysis of Two Contrasting Faiths. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, Inc., 1968.

Anati, Emmanual. Palestine before the Hebrews: A History from Earliest Arrival of Man to the Conquest of Canaan. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1963.

Ariel [Buchner H. Payne]. The Negro: What Is His Ethnological Status? Cincinnati: Proprietor, 1872.

Brenner, Athalya. Colour Terms in the Old Testament, Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series, no. 21. Sheffield, Eng.: JSOT Press, Department of Biblical Studies, The University of Sheffield, 1982.

Bringhurst, Newell G. Saints, Slaves, and Blacks: The Changing Place of Black People within Mormonism. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1981.

Brodie, Fawn M. No Man Knows My History: The Life of Joseph Smith, 2d ed., rev. and enlarged. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1978.

Brunson, James E. Black Jade: The African Presence in the Ancient East and Other Essays. Dekalb, IL: James E. Brunson and KARA Publishing Co., 1985.

Buttrick, George Arthur (ed.). The Interpreter’s Bible. New York: Abingdon Press, 1956, s.v. The Book of Amos, Introduction and Exegesis by Hughell E. W. Fosbroke, vol. 6, 848.

Carroll, Charles. The Negro a Beast or In the Image of God. 1900; reprint, Miami: Mnemosyne Publishing Co., Inc., 1969.

Childe, V. Gordon. The Most Ancient East: The Oriental Prelude to European History. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1929.

Comas, Juan. Racial Myths. 1951; reprint, Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1976.

Copher, Charles B. The Black Presence in the Old Testament, Stony the Road We Trod: African American Biblical Interpretation. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1991.

Crim, Keith (gen. ed.). The Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible, sup. vol. Nashville: Abingdon, 1976, s.v. Slavery in the New Testament by W. G. Rollins.

De Gobineau, J. A. The World of the Persians. Geneva: Editions Minerva S. A., 1971.

De Vaux, Roland. The Early History of Israel, trans. David Smith. Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1978.

Dieulafoy, Marcel. L’Acropole de Suse d’après les fouilles executeés en 1884, 1885, 1886 sous les auspices du Musée du Louvre. Paris: Libraire Hachette et Cie, 1890.

Diop, Cheikh Anta. Origin of the Ancient Egyptians, in Ancient Civilizations of Africa, vol. 2 of General History of Africa. Berkley, CA: University of California Press, 1981.

______. The African Origin of Civilization: Myth or Reality? trans. Mercer Cook. New York: Lawrence Hill and Company, 1974.

Du Bois, W. E. B. The World and Africa: An Inquiry into the Part Which Africa Has Played in World History, enlarged ed. New York: International Publishers, 1965.

Epstein, I. (ed.) Hebrew-English Edition of the Babylonian Talmud, trans. Jacob Shacter and H. Freedman, rev. ed. London: The Socino Press, 1969, Sanhedrin.

Fohrer, George. Introduction to the Old Testament, trans. David E. Green, rev. ed. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1968.

Frederickson, George M. The Black Image in the White Mind: The Debate on Afro-American Character and Destiny 1817-1914. New York: Harper and Row, 1972.

Freedman, H. and Maurice Simon (eds.). Midrash Rabbah, Genesis. London: The Soncino Press, 1939.

Ginzberg, Louis. Bible Times and Characters from the Creation to Jacob, vol. 1 of The Legends of the Jews, trans. Henrietta Szold. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1913,

Glatz, Gustave. The Aegean Civilization, The History of Civilization, C. K. Ogden (ed.). New York: Barnes and Noble, Inc., 1968.

Gossett, Thomas F. Race: The History of an Idea in America. New York: Schocken Books, 1965.

Grant, Robert M. The Bible in the Church: A Short History of Interpretation. New York: Macmillan Co., 1948.

Graves, Robert and Raphael Patai. Hebrew Myths: The Book of Genesis. New York: Greenwich House, 1983.

Harris, Joseph E. (ed.) Africa and Africans as Seen by Classical Writers, The William Leo Hansberry African Notebook, vol. 2 Washington, DC: Howard University Press, 1977.

Hasskarl, G. G. H. The Missing Link or the Negro’s Ethnological Status (borrowed mostly from Ariel). 1898: reprint, New York: AMS Press, Inc., 1972.

Hastings, James (ed.) A Dictionary of the Bible. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1911, s.v. Ethiopian Woman by D. S. Margoliouth.

Heinisch, Paul. History of the Old Testament, trans. William G. Heidt. Collegeville, MN: The Order of St. Benedict, Inc., 1952.

In the Image of God, rev. ed. Destiny Publishers. Merrimac, MA: 1984.

Jagersma, J. A History of Israel in the Old Testament Period, trans. John Bowden. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1983.

Josephus, Flavius. Antiquities of the Jews 2.9 trans. William Whiston, in The Works of Flavius Josephus

Landman, Isaac (ed.) The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Ktav Publishing House, Inc., 1969, s.v. Race, Jewish, by Fritz Kahn.

Larue, Gerald A. Old Testament Life and Literature. Los Angeles: University of Southern California Press; Boston: Allyn and Bacon, Inc., 1968.

Maloney, Clarence. Peoples of South Asia. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc., 1974.

Maspero, G. The Struggle of the Nations: Egypt, Syria and Assyria, ed. A. H. Sayce, trans. M. L. McClure, 2d ed. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1925.

Mellinkoff, Ruth. The Mark of Cain. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1981.

Miller, J. Maxwell and John H. Hayes. A History of Ancient Israel and Judah. Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1986.

Montefiore, C. G. and H. Loewe (eds and trans). Tanhuma Noah from A Rabbinic Anthology. 1983: reprint, New York: Schocken Books, 1974, 56.

Newby, I. A., Jim Crow’s Defense: Anti-Negro Thought in America, 1900-1930. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1965.

Noerdlinger, Henry S. Moses and Egypt: The Documentation to the Motion Picture, The Ten Commandments. Los Angeles: University of Southern California Press, 1956.

Noth, Martin. The Old Testament World, trans. Victor I. Gruhn. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1966.

Oesterly, W. O. E. and G. H. Box. A Short Survey of the Literature of Rabbinical and Medieval Judaism. 1920; reprint, New York: Burt Franklin, 1972.

Olmstead, A. T. History of the Persian Empire. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1948.

Peterson, T. The Myth of Ham among White Antebellum Southerners. Ph.D. diss., Stanford University, 1975.

______. Ham and Japheth: The Mythic World of Whites in the Antebellum South. Metuchen, NJ and London: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., and The American Theological Library Association, 1978.

Prichard, James Cowles. Researches into the Physical History of Man, ed. and with an introductory essay by George W. Stocking, Jr. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1973.

Priest, Josiah, Slavery as It Relates to the Negro, or African Race. . . Albany: C. Van Benthuysen and Co., 1843.

______. Bible Defense of Slavery or the Origin, History, and Fortunes of the Negro Race. Louisville: J.F. Brennan, 1851.

Rawlinson, George. The Five Great Monarchies of the Ancient World, 2d ed. New York: Scribner, Welford, and Co., 1871.

Rice, Gene. The African Roots of the Prophet Zephaniah, The Journal of Religious Thought 36, no. 1. Spring-Summer 1979.

Rowley, H. H. The Servant of the Lord and Other Essays on the Old Testament, 2d ed, rev. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1965.

Sanders, Edith R. The Hamites in Anthropology and History: A Preliminary Study. M.A. thesis, Columbia University, n.d.

______. The Hamite Hypothesis: Its Origin and Function in Time Perspective, Journal of African History 10, no. 4. 1969; 521-32.

Sarna, Nahum M. Understanding Genesis. New York: L Schocken Books, 1970.

Sayce, A. H. Lectures on the Origin and Growth of Religion as Illustrated by the Religion of the Ancient Babylonians (The Hibbert Lectures, 1887), 2d ed. London: Williams and Norgate, 1888.

Silberman, Charles E. Crisis in Black and White. New York: Random House, Inc., Vintage Books, 1964.

Smith, George Adam. The Book of the Twelve Prophets, rev. ed. New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers, n.d.

Smith, Henry Preserved. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Books of Samuel, The International Critical Commentary. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1899.

Smith, Joseph. The Holy Scriptures: Inspired Version and The Book of Moses.

Snowden, Frank. M., Jr. Blacks in Antiquity: Ethiopians in the Greco-Roman Experience. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1970.

Snyder, Louis L. The Idea of Racialism: Its Meaning and History. Princeton, NJ: D. Van Nostrand Company, Inc., 1963.

Tanner, Jerald and Sandra. Mormonism: Shadow or Reality, enlarged ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Modern Microfilm Company, 1972.

Turner, Wallace. The Mormon Establishment. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1966.

UNESCO. The Race Question in Modern Science: Race and Science. New York: Columbia University Press, 1961. In this latter volume, see Harry L. Shapiro, The Jewish People: A Biological History.

Unger, Merrill F. Archeology and the Old Testament. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1954.

Van Sertima, Ivan and Runoko Rashidi (eds.). African Presence in Early Asia, rev. ed. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books, 1988.

Von Rad, Gerhard. Genesis: A Commentary, trans. John H. Marks. Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1961.

Wells, H.G. rev. Raymond Postgate. The Outline of History. Garden City, NY: Garden City Books, 1949.

Whalen, William J. The Latter Day Saints in the Modern Day World, rev. ed. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1967.

Wilson, Robert R. Prophecy and Society in Ancient Israel. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1980.

Winchell, Alexander. Preadamites: Or a Demonstration of the Existence of Men before Adam, 2d ed. Chicago: S. O. Griggs and Company, 1880.

Woodbury, Naomi Felicia. A Legacy of Intolerance: Nineteenth Century Pro-Slavery Propaganda and the Mormon Church Today. M.A. thesis, University of California, Los Angeles, 1966.

Copyright 1998