Theological Ethics, by Gary W. Deddo

Defining a theological ethic

The theological ethic presented here is thoroughly biblical in that it takes into account the whole of the biblical narrative. Rather than picking out individual Bible verses (proof-texting), it considers the entire history of God’s interaction with his creation. Because the focus of that history is the person and work of Jesus, this theological ethic involves taking on the mind of Christ (Isa. 40:13 and 1 Cor. 2:16), which means developing a Christian worldview.

With that mindset, followers of Jesus learn to perceive all reality as being from Christ. From the vantage point of their reconciliation in Christ, they look back to the Fall, then back to creation. They see, as the apostle Paul affirms, that creation was in Christ, through Christ and for Christ. They see that Christ came to save us from our fallen state, corrupted and captive to evil and threatened with destruction and even threatened with falling into non-being. From that vantage point they then look at the present — life in the “present evil age” between the times of Christ’s first and second advents. In this present reality they enjoy the first fruits of reconciliation, taking up their vocation as members of Christ’s body, the church, which is in but not of the world, resisting evil. Finally, they look past the present to our ultimate hope — the consummation of all things when Christ returns to establish fully his rule and reign over all the cosmos, the time when evil will be no more.

Perceiving reality (past, present, future) in this way, our actions, decisions and priorities begin to be formed within the four scenes of the biblical narrative: Creation, Fall, Reconciliation, and Redemption. This is the framework of reality as seen from God’s perspective — a reality that reaches from Ultimate Origin to Ultimate End. From this vantage point, we live out our discipleship in relationship to our Reconciler and Redeemer. This theological ethic (or call it a Christian worldview) accounts for each scene in the narrative, viewing the situation or issue at hand in light of the unfolding of the history of the cosmos in accordance with God’s providential, good purposes put forth in Jesus to re-head (re-unite) all things under Jesus Christ (Eph. 1:10, NET) [1].

The entire story is about the grace of God

God’s plan and purpose to re-head all things in Christ is about the grace of God that comes to us from the good and gracious triune God in myriad ways, though always through Jesus. Creation itself is an act of God’s grace in the sense that it is good and freely given (not earned or deserved). That God has only good purposes for his creation is also a grace. We see this in the creation accounts in Genesis, where we find creation rescued from the undifferentiated darkness of chaos and disorder. God’s grace then unfolds as God gives creation a multi-dimensional structure with ordered inter-relations between a host of parts: sun and moon; regions of water, earth and their various inhabitants; with the arrangement of created things in accordance to their kinds, then ordered within those kinds (e.g., male and female); and ordered within their regions (birds of air, fish of the sea, etc.).

When all these spheres of creation are properly interacting or relating, we find fruitfulness — life leading to more and abundant life. All this reflects the goodness and grace of God. His creation is good — very good, the fruit of the relations of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit: God the Father, speaking through the Word, with the Spirit brooding over it all to bring about a living creation.

Sadly, the good creation of the gracious triune God fell — became alienated from God — resulting in disorder and discord. But God anticipated this event and provided for the reconciliation, restoration and reordering of the created cosmos through the One who would be the offspring of Eve, the One who would crush the head of the deceiving, evil serpent. We later learn in Scripture that this One is Jesus, born of Mary, the second Eve. His birth is not the end of the story, for the ultimate restoration and perfection of God’s good creation comes through Jesus’ life, ministry, suffering, death by crucifixion, burial, resurrection, ascension and sending of the Holy Spirit. And there is yet more to come, which we learn about in the eschatological passages of the New Testament, culminating in what we are told in the book of Revelation.

Living in accordance with a theological ethic

So that’s a theological ethic — more precisely, a Christian theological ethic. But how do we live it out in daily life? The answer is that we do so by thinking with the mind of Christ, which means taking fully into account the four scenes in the aforementioned biblical story. Grounded in that narrative, with its focus on who God is and therefore who we are in relation to God, we note the Bible’s many commands and directives related to ethics. Though we understand that these instructions are not arbitrary, we note that they are given in a particular context, namely that of the outworking of the grace of God in creation, the fall, our current state of being reconciled and being sanctified, and in hope of ultimate redemption (the aforementioned four scenes in the biblical narrative).

Within the context of this narrative framework, the Bible addresses what it means to be a human being who lives in right relationship with others, in ways that glorify God. In Scripture we find a rich, multi-leveled unfolding of what it means to be a human created according to Jesus Christ, the image of God, and of our being recreated according to that image as members of the body of Christ in hope of ultimate redemption. That revelation, when put together within the narrative framework, fills out the indicatives of grace (statements about who we are in Christ, our identity), which gives rise to the imperatives of grace (God’s instructions concerning ethical behavior). This grace-based, Christ-centered revelation then shapes our thinking concerning all matters of ethics. Below is an example of this shaping as it pertains to sexual ethics.

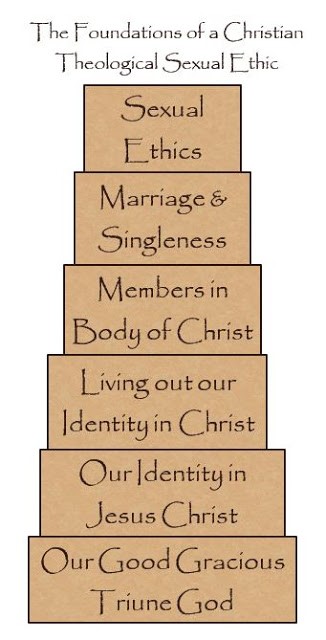

Let’s unpack the diagram above, one level at a time:

- Level 1: We begin at the bottom of the diagram with the essential foundation — the triune God, who we know to be good and gracious. This is where all truly theological reasoning begins. We are reminded here that all human beings were created by this God, according to Jesus, the God-man who is the true image of God.

- Level 2: Here we are reminded that we humans have our being, our identity in Jesus. In him we have our belonging, meaning, significance, security and destiny. Jesus (whether we know it or not) is our life.

- Level 3: Here we see that we are to live out of (in accordance with) our identity in Christ, an identity given to us as a gift of grace. This living involves how we relate with both God and people; it involves our relationship with ourselves and everything else.

- Level 4: Here we see that we live out our identity in Christ as members of his body, the church. Ethics in all areas of life involves living in community.

- Level 5: Here we see that it is within the structure established by the first four levels that we then (and only then) identify as being married or unmarried (single).

- Level 6: At this level, which is built upon (and so grounded in) all that underlies it, we arrive at a comprehensive theological sexual ethic.

The commands, instructions and exhortations found in the New Testament make little sense unless viewed from the perspective that is indicated by the above diagram with its six levels — a perspective that speaks to God’s intentions for humanity, including the reconciling work of Christ in answer to the fall. It is in accordance with this theologically-formed ethic that we are able to practice in matters pertaining to sexuality (as well as to other ethical issues) what the apostle Paul refers to as the obedience of faith (or the obedience that comes from faith) (Romans 1:5; 16:26).

What is truly ethical is that which reflects in a human way the glory that belongs to the triune God. The ethical directives and standards given in Scripture might seem arbitrary when viewed apart from this context. But seen within this framework, they make sense, for they have to do with the goodness and grace of God, which upholds, orders, and renews the structures of the fallen relationships in which we now live, as they hold out the promise of the fulfillment of God’s intentions with the coming of the renewed heavens and earth.

Human pride unchecked tends to regard God’s will as a violation of human rights and freedom. But the Holy Spirit leads us to proclaim God’s good will (his ethics) on the basis of their theological foundations — foundations that point to the indicatives of grace (our identity in Christ). Indeed, the only hope of rightly understanding God’s ethical directives is knowing who the Commander is, namely the Creator, Redeemer and Perfecter of all that is. We hinder, even undermine, faithful obedience to God’s good will when his commands are not presented within this theological context, and so there is the need for the development of a theological ethic (a Christian worldview).

_______________________

[1] The NET Bible provides the following footnote on the phrase “head up” found in Eph. 1:10, NET:

The precise meaning of the infinitive ἀνακεφαλαιώσασθαι (anakephalaiōsasthai) in v10 is difficult to determine since it was used relatively infrequently in Greek literature and only twice in the NT (here and Rom 13:9). While there have been several suggestions, three deserve mention: (1) “To sum up.” In Rom 13:9, using the same term, the author there says that the law may be “summarized in one command, to love your neighbor as yourself.” The idea then in Eph 1:10, NET, would be that all things in heaven and on earth can be summed up and made sense out of in relation to Christ. (2) “To renew.” If this is the nuance of the verb then all things in heaven and earth, after their plunge into sin and ruin, are renewed by the coming of Christ and his redemption. (3) “To head up.” In this translation the idea is that Christ, in the fullness of the times, has been exalted so as to be appointed as the ruler (i.e., “head”) over all things in heaven and earth (including the church). That this is perhaps the best understanding of the verb is evidenced by the repeated theme of Christ’s exaltation and reign in Ephesians and by the connection to the κεφαλή- (kephalē-) language of 1:22 (cf. Schlier, TDNT3:682; L&N 63.8; M. Barth, Ephesians [AB 34], 1:89–92; contra A. T. Lincoln, Ephesians [WBC], 32–33).

A theological ethic, part 2

There is a tendency to approach obedience to God’s directives and instructions in one of two misguided ways. The first is legalism — seeking through obedience to earn God’s favor, thus overlooking the reality that God’s grace underlies all of God’s commands. The second misdirected approach is antinomianism — treating God’s commands as arbitrary and thus subject to being re-worked or entirely dismissed. Both approaches undermine true biblical obedience, which the apostle Paul calls the obedience of faith (or the obedience that comes from faith) (Rom. 1:5; 16:26). Legalism and antinomianism both arise when the commands of God are detached from their biblical context — their grounding in the grand narrative of God’s plan for humanity with its four scenes: Creation, Fall, Reconciliation and Redemption.

A theological ethic carefully accounts for the entirety of this grand narrative, including our part in it via a living, grace-based relationship with God through Christ. It is within this grace-based, gospel-shaped context that we see God’s commands not as onerous (the fruit of legalism) or as arbitrary (the fruit of antinomianism). Instead we see his commands as imperatives of grace (how we are to live in Christ) that flow from the indicatives of grace (who God has made us to be by grace, in and through Jesus). We arrive at his understanding when we rightly interpret the Word of God, which includes understanding its ontological center, which is the being and act of God in Jesus Christ.

Concerning obedience and disobedience

Let’s now look at why obedience to God’s will (including his commands, directives and instructions) is always good. We begin by noting that, in all instances, disobedience to God’s will has negative consequences of one sort or another, to one degree or another. Why is this so? Because God’s will for us always conforms to the real nature and purpose of things — the moral order that God has placed within the cosmos of his creation. Disobedience (sin), in one way or another, always is out of sync with this reality. It is a violation of the God-ordained moral order of reality.

When a person acts in a way that is not in accordance with this moral order, some kind of harm results, some relationship is damaged, some fruitfulness is hindered, some deceit is reinforced and spread. Note that this damage done through disobeying God’s commands does not require the consent of the sinner. Sin is like a disease that damages whether the disease is diagnosed or not. The disease certainly won’t be cured by denying its presence or by insisting that it is health, rather than disease.

Some justify disobedience to God’s commands by labeling disobedience an expression of love. This approach typically involves reducing love to kindness. But love cannot be reduced to mere kindness. Love is concerned for the actual health of the object of love, and seeks to avoid or at least minimize damage to that object (including oneself). Such love can be risky, in that it risks offending the pride of the one being loved. On the other hand, kindness risks little, typically being concerned primarily with avoiding offense.

The point here is that disobedience to God has consequences. When people give into temptation to disobey God, they are colluding with evil, buying into the lies of the Evil One. When that occurs, damage always results. Sin is not a mere “no-no,” nor is it merely ignoring a rule arbitrarily given by a god who enjoys controlling and manipulating people.

The pitfalls of a modern worldview

Living in accordance with a theological ethic inevitably brings us into conflict with the modern Western worldview — a mindset that declares humans to be entirely free in their own existence. They are seen as free to do whatever they want, and free to avoid unwanted consequences, since consequences are mostly, if not entirely, in the mind — imagined, not real.

According to this mindset, right and wrong, obedience and disobedience, are entirely subjective (personal) matters. We humans are thus free to relabel things in any way we choose, so as to align them with our personal preferences; our subjective sense of what is right and wrong. In short, we can do anything we want. According to this worldview there are no limits to the subjective powers of the human individual.

The truth, however, is that sin has a real objective side to it. Sin has real consequences that are not subject to human minds or free-will escapes. Much suffering in the world occurs because many people have bought into the lie that their actions and choices do not or should not have unwanted consequences — the view that everything can be easily fixed or worked around. But then reality steps up and bites us and we don’t understand why life is so hard, so unfair, so lonely, so anxious, so guilt-ridden, so full of shame. So we try to eliminate these unwanted consequences of sin through willpower. We imagine that we should be unaffected by such things. If we are, then someone else is surely to blame! Someone else is trying to make us feel guilty, make us feel ashamed, make us unhappy or unfulfilled. Such people are thus seen as our enemy — surely the problems we are experiencing could not be something about us!

On dealing with sin and its consequences

Try as we might, the consequences of sin are unavoidable. That’s reality. That’s the bad news. However, there is good news — sin can be acknowledged and forgiven. There is healing — a movement toward wholeness by the grace of God, which is available to all. But experiencing that wholeness down to its very roots depends upon recognizing sin for what it is, then going to the Real Source of forgiveness, reconciliation and restoration. Attempting to get rid of guilt and shame by simply denying there is sin and evil does not work.

One of the most regularly promoted ways of dealing with guilt and shame is to blame others. Others make me feel guilty or ashamed, it is claimed. I’m innocent, we protest. That too, is a lie. Yes, there is false (unwarranted) guilt and shame. Sadly, there are those (most notably the Evil One) who use guilt and shame as a weapon to control and manipulate others. These situations must be discerned and dealt with. But blaming others, even when they are to blame, does not bring much healing and restoration. That takes a much deeper work by the Word and Spirit of God. This is what the church uniquely has to offer — getting down to the root of the problem and the real solution even if the fullness of healing is not experienced in this life.

The church’s responsibility

Out of agape love (which goes far beyond mere kindness), the church warns about sin, not to manipulate or control, but because sin has consequences — it does damage. The church therefore warns individuals and warns human authorities. It attempts to shape organizations and institutions around the moral order of things as revealed in Scripture.

Though the church must never use coercive power to try to force obedience on individuals or groups, it should, in love, inform, persuade and influence by lawful means concerning what is good and right in relationships. Moreover, the church, again in love, should, when necessary, use church discipline with its own members. Numerous biblical passages indicate just this, and tell us something of how to go about administering discipline. It would be less than loving for the church to stay silent — like a doctor knowing a patient is seriously ill, but not saying so because it might offend the patient, or might lead to some suffering in order for the patient to be healed.

The New Testament is clear that the church, at times, must make judgments and take action. But how this is done is critical. Unfortunately, there have been times in which the church has bought into the false idea that it does not matter how it treats sinners as long as it’s sure sin is present. This amounts to the false idea that one can treat a sinner sinfully. No! Scripture is clear on how sinners are to be treated. Warning and correction must be carried out with gentleness, patience, and by giving incremental warnings with compassionate persuasion. Church discipline is to be administered with hopefulness in Christ, because the love of Christ will be what compels and guides it. See the book of Philemon for a good example of this.

Love the sinner but hate the sin?

In reaction to the times the church has treated sinners sinfully, some object to the church taking any action in response to the presence of sin. It’s common for them to object to the often-stated maxim that Christians are to “love the sinner but hate the sin.” What about that idea? Scripture does make it clear that we are to hate what is evil. In Romans 12:9-10 Paul shows us that love and hating evil fit perfectly together. For Paul, evil is diabolical, deceitful and damaging, so it must be repudiated. Moreover, we are to hope for the day when evil will be no more.

If it were impossible to both love the sinner and hate their sin, there could be no salvation, for God will either have to love us and love the sin too, or hate us as well as the sin. Or God would have to deny there is such a thing as sin and evil and so leave everything just as it is, and cease to be good himself.

Grace is the definition of God’s hating the sin and loving the sinner and so rescuing him or her from the guilt of sin and the power of evil. If we are our sinful actions and we cannot be separated from them, then there is no salvation. Grace condemns the sin (judges it for what it is), cuts us apart from it, and rescues us sinners from it, cleansing, freeing and redeeming. That is what salvation is! That is why Paul so emphatically states that grace never means that sin should continue and abound. Grace makes no exceptions to sin. It’s all got to go. Can you imagine what our eternal state would be if grace just made exception after exception to let sin in with us into his eternal kingdom? What would that be like? I think you know. If there is salvation, there has to be a real difference between sin and the sinner.

Perhaps it’s important to make one qualification here. We don’t have to use the word “hate” when thinking or attempting to explain this, even though the Bible does. Hate in the biblical context does not always have the connotations that modern Western people think it has. Hate does not mean to wish evil upon someone, have ill will, to justify treating someone in any way one pleases, including physical harm, verbal attacks, etc. Rather, it means to reject or separate oneself totally from the sin, to not come under its influence or to be obligated in any way to it or be controlled or dominated by it. To hate sin is to repudiate association with it. So we can modify what we might say, and say something like this instead: “God rejects the sin and while loving and forgiving the sinner.” I have often put it this way: “God in his grace accepts us wherever we are, to take us where he is going. In his transforming love he never simply leaves us where he found us, for that isn’t truly loving.” Isn’t that in line with what Jesus said? “Neither do I condemn you. Go and sin no more” (John 8:11).

Part 3

Developing, then living out an ethic that is God-centered (theocentric) rather than human-centered (anthropocentric) is a great challenge. Why? Because the worldview (mindset) prevalent in our modern/postmodern West is fundamentally anthropocentric, leading to an ethic that is largely pragmatic, utilitarian and even hedonistic. So how do we as Christians, in this cultural setting, develop, then live out a truly theological ethic? A good place to begin is in the Gospel of Matthew:

A lawyer asked him a question to test him. “Teacher, which commandment in the law is the greatest?” He said to him, “‘You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind.’ This is the greatest and first commandment. And a second is like it: ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets.” (Matt. 22:35-40, NRSV)

Theological ethics and the great commandments

According to Jesus, these two commands summarize the will of God for humankind as presented in Holy Scripture (“the law and the prophets” is a reference to the Hebrew scriptures, what we refer to as the Old Testament). Much can be said about Jesus’ statement, but let me address an issue that is at stake in our day. Some speaking within the church, along with some outside, say that the church should focus on the second of these two commands. In effect, they advocate collapsing the first into the second, with the result that the second command is made into the first and only command: Love your neighbor. This move, which is a subtle perversion of the core of Christian ethics, is a form of idolatry.

The primacy of the first great command

Though Jesus speaks of two great commandments, they are not equal. One cannot be collapsed into the other, especially the first into the second. Why? Because God is not my neighbor and my neighbor is not God. The command to love God is unique, applying to no one and nothing else. We are to love God with all that we are and all that we have — body and soul, mind and heart. There is nothing that is a part of a human’s existence that is not to be devoted to loving God. This command is telling us about the true worship of God. God alone is to be worshiped — to be loved in this total and complete way. Loving anything else in this way is false worship, or idolatry.

When we treasure God with all we are and have, when we love (agape) this God with all we are and have, we are participating in a worship relationship. And there is to be only one worship relationship, and that is with the one and only God. All else is idolatry. This first commandment involves a one-of-a-kind relationship that no other even dare approach. This love is unique because of its unique object: God, our Holy Triune Great I am, the incomparable One, the one and only Creator, Redeemer and Perfecter—the Lord God, YHWH. This God alone is worthy of the love that is worship. Worship of anyone or anything else with this kind of love is blasphemy, is evil.

We humans have an exceedingly hard time dealing with what is unique, which has no comparison, which is truly one of a kind. But that is exactly what is true of God. There is no other God, and a right relationship with this God is incomparable—one of a kind. This is not an exaggeration, a hyperbole. It is literally, realistically true.

Jesus came to seek worshipers of the Father (see John 4, the account of the woman at the well). He came so that we could share in his true worship of the Father in Spirit and Truth (see the book of Hebrews). That meant he came so that we might love God, as Jesus loved God with all he had and all he was — heart, soul, mind and strength. That worship included Jesus absolutely trusting in and lovingly obeying the Father — in our place and on our behalf. We are to serve no other Master, Jesus tells us. He came to take us to the Father and to send us his Spirit.

As Jesus tells us, eternal life is to know the Father through him (John 17:3). Jesus’ central mission was to reconcile God’s own sons and daughters to him through his atoning death and to destroy the source of all rivalry to the worship of God alone. Evil is represented by the Satan, the deceiver. Jesus is our great High priest, our Leitourgos (leader of liturgy/worship), our one true worship leader. He came to enable us to be true worshipers of the Father in the Spirit through him, the Son.

Jesus, the eternal Son of God, is the one true worshiper. He alone, in our place and on our behalf as one of us, fulfilled the first and greatest command. He alone has perfectly loved the Father in complete worship, with his whole life, from birth to death. That is the law of love that Jesus fulfilled — and he did it bearing our fallen nature (flesh) for us so that we too might join him in his perfect worship, in his perfect and complete love for the Father in the Spirit.

Sadly, the moral crises that we see around us tempt many Christians to neglect the first command and to focus on the second. This amounts to having an anthropocentric ethic rather than a theocentric ethic. But our lives are not really about us humans (individually or collectively). We were created to be worshipers. That is our meaning, purpose, significance, our destiny. Our worship is our expressing of perfect and complete love for God — which we can have only by sharing in the Son’s perfect loving, trusting, obedient worship of the Father in the Spirit.

Roots of the problem

The separation of the second command from the first, resulting in a focus on the second, is not new. It got a huge boost in the 19th century within the “liberal” church. Influential teachers, such as Adolf von Harnack, insisted on making Jesus into the greatest moral teacher ever to live. It mattered not at all who he was. What counted was the moral code that Jesus gave. But given this approach, anyone else who taught the same code would have accomplished all that Jesus did. Jesus was simply a messenger with a moral message — nothing more, nothing less. Harnack reduced Christianity to an ethic, summarized by saying that the real Jesus behind the misrepresentations of the New Testament taught nothing but “the Fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man.”

Collapsing the first great command into the second, which is more and more common in our day, has the same result. After all (it is falsely reasoned) both commands are about love (never mind that the objects of love in the two commands are not the same!), thus they are interchangeable. Indeed, they must be interchanged! Why? Because the only way you can prove or demonstrate love for God is by loving your neighbor. After all, how can you love God you can’t see? To back up this false reasoning, Jesus, along with his ethical teachings, is brought forth as the greatest human example of love for other humans. According to this line of reasoning, we are to follow Jesus’ example of doing good and loving others and to follow his moral teachings. What that requires of us is merely an act of will to treat our neighbor like Jesus did. That is the only way to love God, and so fulfill the requirement of the first commandment. A human moral example and moral instruction is all that is needed.

But notice what has happened in this faulty line of reasoning: our neighbor is put in the place of God. Our neighbor becomes the sole object of love. Those who embrace this line of reasoning would deny that one’s neighbor is divine, though this reasoning implies that humans are worthy of ultimate love and devotion. Equating love for God with love for neighbor eviscerates the worship of the Transcendent God. In essence, it denies direct contact with God. It tends to place God at a deistic distance from us. It says that if there is a God, he gave the world a moral and physical order, then left it up to us to make the most of it. All that is left as an object of our devotion and love is humanity — our neighbor. In short, humanity is deified, and Jesus and the Bible are used to justify this switch.

The net effect

When, for all practical purposes, God is thrown out of the picture and a transcendent moral order thrown out with him, human beings put themselves, by default if not by deliberate intention, in God’s place. Now deserving the greatest love conceivable, which was once reserved for God, there is little to nothing stopping human beings from becoming tyrants, individually or corporately. With no God in sight, human beings become ultimate ends in themselves. They determine what they want, what they need, what they deserve. Humans set the terms for the deification of themselves, they become their own lords. Being autonomous from any God, humanity now is free to idolize itself. It can use the Bible to justify this move (if it needs to) by simply equating the two great commands, making them interchangeable, then declaring that the only way to love God is to love one’s neighbor.

Though not all parts of modern Western culture have fallen to this level, it seems to be in free-fall. Our culture-shaping institutions have, for the most part, broken free from any real Christian influence and conviction. Sadly, much of the church has not only followed suit, but promoted this deistic moralism, which is attributed to Jesus as a human ethical teacher.

This anthropocentric mindset of autonomous human beings attempting to be ethical on their own terms plays out on a smaller scale in the lives of individual people. When love for God is the same as love for neighbor, then the neighbor can demand anything. Refusing the neighbor anything they want is to cease to love them, for love has come to mean granting unquestioned concession to an individual’s wants and desires. Anything that might upset an individual’s equanimity, such as questioning their integrity, offending their pride or their tastes, is regarded as a violation of their very beings, a hindrance to their absolute right to pursue life and liberty. Any repression or suppression (following Freud’s ideas) is evil, since love for a human being requires granting each one absolute free will — limited only by the absolute free will of another autonomous individual.

Some are now even claiming that everyone has a right to do wrong. No one can be questioned because there is no basis for doing so. Each is a law unto themselves. Each one is a god, with the right to do “what is right in his own eyes” (Judges 21:25). Everyone determines for themselves what the pursuit of happiness will be for themselves, and no one has a right to get in the way — for that would be a violation of their humanity. Each human being is answerable to themselves and for themselves only. That alone is what is good and right.

This perspective, which is characteristic of a modern/postmodern Western, secular worldview has, unfortunately, fed into plenty of contemporary Christian ethical thinking. It would seem that the only option to God being a tyrant himself is to imagine a god who is a means to our humanly fabricated ends. Fulfilling that role, Jesus is depicted as a man specially gifted by God to be a moral example of love. He does so by serving others on their terms and giving them whatever they decide they need, whatever they want. If we are to love others as Jesus did, we would give others whatever they needed/wanted, never judging anyone, since we are in no position to withhold, question or even warn anyone. Each one stands entirely on their own. In this line of thinking, one’s neighbor is an autonomous object of ultimate love.

In this flawed anthropocentric ethic, the will of God is reduced to love for other human beings, though that love is actually being reduced to kindness. What is good and true, right and meaningful, is relative to every individual. Accordingly, the first law of love becomes the obligation to be “true to yourself.” For only then will you be true to the divinity within you. Only that which is external to you can corrupt you, turn you from your true destiny and self-realization. Internally, we are pure, good and incorruptible. All we need to do is arrange external circumstances to let that divinity shine forth in all its natural glory.

This anthropocentric ethic represents a humanistic ideal. It is not workable, because when everyone is given carte blanche, you end up with a hoard of gods competing for limited goods and opportunities. Since all values are relative, the result is social chaos, self-justification and a lot of self-righteousness. Making the two great commands equal, collapsing the first into the second, is a recipe for not only spiritual disaster but also social disaster. Sadly, that seems to be where our culture is headed.

Part 4

Worship only God

We have noted the danger of collapsing the first great command (to love God) into the second (to love neighbor). Though doing so is common in our modern/postmodern world, as followers of Jesus, we must understand that it is a form of idolatry, which God forbids. We are to worship only God, and no other — a command Israel, sadly, never fully obeyed, despite years of being chastened by wilderness wandering and exile in Babylon.

Though the two great commands go together, they are radically different in that the two objects of love (God and neighbor) are very different and therefore cannot be interchanged and must not be confused. Why is this important? Because God is not a human being (even though the eternal Son of God, without ceasing to be divine, assumed to himself our human nature). The first command calls for the kind of love for God that is worship and we, as Christians, are to worship God alone. Worship of a created being (a creature) is, by definition, idolatry. No creature is worthy of our worship.

Getting the commands in the right order

The first command thus puts love for God in its rightful place, demanding first and foremost the devotion of all we are and have. It calls for a worship relationship. And such a relationship cannot, for any reason, be demoted to a position equal to another, or eliminated. It cannot be interchanged with any other command any more than God can be interchanged with the neighbor or one’s self.

If that is the case, we might wonder, how can there be any love left for anyone else? An all-consuming love for God seems to make it impossible to love anyone else. We might reason that there’s only so much love to go around, so it needs to be divided up, proportioned. If we’re going to love people at all, then, we must love God at least a little less. Such an all-consuming love for God seems unreasonable. It takes away love for others.

Jesus does not reason in that way. His life demonstrates that love for God does not work that way. When we love God with all we are and have, there shines forth a reflection of it towards those who are not God. We love God because God first loved us (1 John 4:19). Our love for God is a response, the right and appropriate response, to God’s love for us. We first receive God’s love and we first love God. When we love the neighbor in the way God would have us, then like Jesus, we are passing on to others what we have received from God. Think of the offering of the Lord’s Supper and Paul’s words: “For I received from the Lord what I also handed on to you” (1 Cor. 11:23). In God’s economy, we can pass on only what we have first received. First things must remain first, otherwise, as C.S. Lewis reminds us, we will lose both the first and the second things.

The second command depends upon the first. It is not identical to it, and it is not interchangeable with it. We see this not only in the fact of the difference between God and neighbor, but in the designation of the second command as not identical with, but “like” the first — comparable to it and having a similarity to it, but not the same. The two commands are related, yet distinct. Love for neighbor reflects something of what takes place in love for God (a response to God’s love for us). The love we receive from God, then give back to God, is mirrored (reflected or imaged) towards others. Note, however, that in this there is strict recognition that the neighbor is not God. Our neighbor is not to be loved with all our heart, soul, mind and strength. That sort of love is reserved for God, and no other. The neighbor is not to be worshiped, for that would destroy them or the worshiper, or both.

Our neighbor can be loved with the love that we receive from God as we love God with all our heart, soul, mind and strength. But we love our neighbors not as God, but as neighbor. We love them in a way that mirrors God’s own love for them — and that is not a worship relationship. God does not worship his creatures, but he does love them as his creatures. That is why I believe a true rendering of the last part of the commandment can be stated this way: Love your neighbor as you yourself are loved by God. The word “as” is important as is the word “like.” It means in a similar or comparable way. We cannot love others in exactly the way God loves them even as creatures. But by the grace of God, we can share in Jesus’ love for our neighbor. Jesus lays the whole thing out in a few words. He tells us first “As the Father has loved me, so I have loved you.” Note the comparative word “as.” Then he goes on to say, “As I have loved you, so you ought to love one another.”

A three-fold love

In the biblical testimony we find a three-fold love, where (as shown in the diagram below) each subsequent love mirrors or reflects the originating love.

Love for neighbor is constrained by love for God as God. Our definition and source for love comes from and is maintained from above by God and God’s word. We do not define what is loving towards neighbor (and neither does the neighbor). God’s agape love designates, directs and defines what is loving towards neighbor, who is not God but who has a God, a creator, a redeemer. They have a God-given purpose and a God-given nature and a God-intended destiny. The neighbor is not autonomous. The neighbor is not a dictator to us. This does not mean that we cannot listen to the neighbor and even sympathize. But what is good and right will ultimately come from the command of God in accordance with the moral order of love, even while taking into account what we hear from the neighbor and grasping their plight.

We serve others not in their own names, but in the name of Jesus Christ, Lord and Savior. We serve others by doing the loving and good will of God towards them as a representative of Jesus himself (the true Jesus, not merely our idea of him). Such serving of neighbor might include giving a word of warning, a word of forgiveness that implies their need for forgiveness and their need to receive it by repentance. We do not serve the neighbor as our master. We serve them as servants of Jesus, and of no other. We serve others on the basis of our worship relationship with the living God. We become the slaves of no person, yet we freely serve others—in Christ’s name, in his place, and on his behalf.

When we seek to fulfill the first command, we are resourced and freed to pursue the second. The first orders and generates how we fulfill the second. Our worship relationship to God overflows into the secondary relationships with others. Fulfilling the first command fully, Jesus was free to violate the expectations of many people and rather to love them and serve them in the way the Father loved and served him and not be enslaved to the (fallen, self-serving) wills of those he came to serve and transform.

The example of Jesus

When unbelief prevailed, Jesus refused to do any miracles, and many took offense (John 6). Even his immediate family was offended at times. He sternly warned the Pharisees and Sadducees regarding their false teachings that misrepresented God and relationship with God, even calling them “whitewashed graves.” He pronounced forgiveness of sins to those who were not looking for it. He delayed coming to heal Lazarus and was chastised by all for doing so. He refused to stay in a town to do more healing, but went on to others in order to preach, “for that is why I came.” He refused to give signs to those who rejected the Reality standing in front of them to which the signs pointed (Luke 11:29). He did not feed all or heal all. Jesus chided the man sitting at the pool who wanted to complain and give excuses when his Healer stood before him and addressed him in person. He offended the Pharisees by receiving a repentant sinner who sought fellowship with him. He scandalized religious leaders and some of his own followers when he allowed a repentant and believing woman of ill repute to anoint him with very costly oil, which they said could have been used to benefit the poor (Mark 14).

Jesus shamed the elders who tried to trap him and get him to condemn a woman caught in adultery. He would not answer Pilate, who threatened him, but rather rebuked him for thinking that he had power over him. The sufferings imposed upon him did not stop him from accomplishing his atoning purposes. Rather, he scorned the shame heaped upon him. He offended some of his listeners when he compared God to one who gave unequal wages to persons, being more generous to some than they deserved. He told Peter to stifle his heroics and put away his sword. He let Peter know that Satan was using him when he declared that Jesus, God’s Messiah, should never suffer and die. But then, Jesus assured Peter of his restoration.

Jesus refused to follow the demands of the Zealots to overthrow Rome and paid for his resistance with the betrayal of Judas into the hands of those whom Judas despised. Jesus “would not entrust himself to them, for he knew all people. He did not need any testimony about mankind, for he knew what was in each person” (John 2:24-25). He recognized rejection and unbelief towards him and in his Father, and he grieved over it. Jesus prepared his own disciples to deal with the rejection they would experience when serving others in his name and in his way, for the sake of the gospel.

Jesus was not crucified for being nice and kind, and doing good things. He was crucified because of his absolute loyalty, love and worship of God, and how that exposed human hypocrisy, deceit and captivity to evil. True to God, Jesus uncovered the works of darkness, and confronted deceit and evil. He exorcised demons. He forgave sin because sin required a costly forgiveness to be defeated, undone, brought to a complete end. Jesus took every excuse away from those who refused to repent and to worship God and no other.

Jesus became a rock of stumbling and an offence to many, that is to anyone, Jew or Gentile, who would not repent and believe in the Son whom God the Father had sent in the power of the Spirit (1 Peter 2:8; Romans 9:33). He did all of this because of his holy love for all and his desire for all to come to the point of repentance and receive their forgiveness and be reconciled to the one who was already reconciled to them (2 Cor. 5:20).

The example of the apostles

It was no different in the early church. The apostles preached Jesus crucified by evil and resurrected from the dead by God, who was absolute Lord and Savior over all. They preached the absolute need for reconciliation that can come only from God, and they pronounced the forgiveness of sins that was available through the cross of Christ and received by repentance and faith/belief in him. Peter and Paul were beaten by fellow Jews, jailed by Roman authorities and eventually put to death for disobeying the authorities’ commands, continuing to preach the Lordship of Jesus Christ over against the lordship of Caesar.

The apostles did not dispense what everyone “naturally” wanted. Peter told a beggar: “I have no silver or gold, but what I have I give you; in the name of Jesus Christ of Nazareth, stand up and walk” (Acts 3:6). According to the hierarchy of human need (actually a hierarchy of human hedonism) defined by psychologist Abraham Maslow, the beggar should have rejected (or could not have received) what Peter gave, since it ignored his more fundamental material “need.” Apparently, Jesus did not recognize this hierarchy of need since he sent out his apostles with nothing of earthly value (bread or money — see Matt. 10:9; Mark 6:8) to offer people the proclamation of Jesus Christ incarnate, crucified and resurrected; and to call them to repentance and belief in Jesus, including trust in his coming kingdom.

The apostles maintained these priorities in leading the church, “preaching the word of God” instead of “serving tables.” They arranged for others (deacons) to address those needs (Acts 6:2). They did not change the message concerning Jesus when hearers were put off or offended, even to the point of wanting to stone them. They realized that the gospel always offends human pride: “The message about the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God” (1 Cor. 1:18). “Jews demand signs and Greeks desire wisdom, but we proclaim Christ crucified, a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles, but to those who are the called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ the power of God and the wisdom of God (vv. 22-24). The Gospel always fulfills and offends some people. There is no way to avoid this. This is how they viewed their ministry and why they stayed true to the message of the gospel and to their Lord. They remained faithful and would not be compromised.

Thanks be to God, who in Christ always leads us in triumphal procession, and through us spreads the fragrance of the knowledge of him everywhere. For we are the aroma of Christ to God among those who are being saved and among those who are perishing, to one a fragrance from death to death, to the other a fragrance from life to life. Who is sufficient for these things? For we are not, like so many, peddlers of God’s word, but as men of sincerity, as commissioned by God, in the sight of God we speak in Christ. (2 Cor. 2:16)

Our calling

We seek to follow Jesus and his apostles in fearlessly proclaiming the gospel. But a word of caution is in order — we must never pronounce the ethical commands (instruction, teaching) of God detached from their gospel context. The gospel message (the apostolic word) addresses our deepest and primary need, which is to be reconciled to the God who already, in Christ, has reconciled us to himself and provided all we need for responding back to God. Any ethical command must be proclaimed in this context — the context of who God is and what he has done, is doing, and will do for us, and who we are, in and through Christ, in relationship to the triune God. In short, we must first proclaim the first command, and then show how obedience to the second command flows out from a worship relationship with the triune God revealed in Jesus Christ.

The second command should never be proclaimed apart from the first. The second can be understood only in light of the first regarding the triune God, who first loved us so that we can then love him with all we are as expressed in our worship of him. Then, out of that worship relationship with the triune God, we are prepared to serve (love) others in his name and in his way — the way that directs others to the One who we are to worship, and no other. In that way, we join Jesus in his primary mission of bringing others into a worship relationship with the one true Triune God.

Part 5

Our calling as followers of Jesus is first to worship God (and no other), then out of that relationship of worship (loving God), to love our neighbors (sharing in God’s love for them). By worshiping only God, we avoid a form of idolatry that is common in our day — the collapsing of the first Great Commandment (to love God) into the second (to love neighbor). Let’s look further at how a theological ethic protects us from this idolatry. We begin with Jesus’ example.

Jesus’ example of sacrificial giving

Throughout his life on earth, Jesus showed perfect love by sacrificially giving of himself. He first gave himself in faithful, even joyful obedience to his Father. Then, as part of his worship of the Father, Jesus gave sacrificially of himself to us. It was out of total trust in and honor to his Father that Jesus loved and served us. Jesus serves us only in ways that take us to the Father.

It was because Jesus knew he was in right relationship to his Father and the Spirit, and because he knew where he had come from and was returning, that he served us in the ways he did. This truth is explicitly illustrated in John’s presentation of Jesus’ washing of his disciple’s feet at the Last Supper — an act by which he “loved them to the end” (John 13:1). In this act of love, Jesus was fulfilling both of the Great Commandments in the right order, priority and inter-relationship. Understanding sacrifice as an act of the worship due only to God, Jesus did not allow Peter to dictate how the foot washing should occur. Jesus veered neither to the right nor the left in fulfilling the Father’s will. In doing so, Jesus resisted and offended Peter (and perhaps others).

Jesus’ disciples had to receive what Jesus was actually giving them, not something else they might have preferred — something that might not have offended their pride. Had Jesus yielded to their preferences, he would not have “loved them to the end” — to completion. Rather, he would have loved them less and perhaps not at all. It was only as an overflow of his sacrifice to God and to God’s good will and glory that Jesus “sacrificed” himself for us, not to us — not bending his will to our will and ways and ideas of what we might consider to be loving. Self-sacrifice is due to God, our Creator and Redeemer, and to no one or nothing else. That is what Jesus’ example makes clear.

Self-giving to others in Christ’s name, for God’s glory

Jesus Christ, and no other, is our Creator and Redeemer. We were created to be and become images of him and of no one and nothing else. So, it is the same for us as it was for Jesus in his earthly ministry. Any self-giving for another human being must be motivated, guarded and controlled by our self-surrender to God first and alone, in worship. Love for neighbor certainly will involve self-giving and in that sense self-sacrifice. However, that sacrifice will never be to the neighbor — it will be for the neighbor as our worship of God, as his commands to us specify. Directed toward worship of God, our “sacrificial giving” will glorify God while also contributing to the true benefit of our neighbor. Any of our “sacrificing” must be done in the name of our Triune God, not in the name of our neighbor.

Sacrificial giving that does not come under the discerning and sanctifying light of the worship of God, following in his ways, results in faulty, even evil “sacrifice.” There is nothing Christian about the idea or ideal of sacrifice itself. Pagan religions are full of it — with the ultimate (most grotesque) expression being the sacrifice of children to the god Molek (2 Kings 23:10).

As in religion, so it is in relationships — sacrificial giving can become a means to manipulate, entrap, ensnare and place in endless obligation the one for whom the sacrifice is made. Conversely, the demand for sacrificial giving as an ideal held up for others to live by, can be tyrannical and even demonic. Jesus himself had to resist exactly this kind of sacrificial heroism as a way of obtaining the earthly goods offered him by the devil. Jesus said No! every time. He refused any self-sacrifice to the devil.

When Jesus is offered as a mere generic example for us to imitate, his sacrifice is torn apart from his exclusive worship of God, and redirected to establish an abstract and autonomous human “ethical” ideal — one that inevitably enslaves and even destroys the one who sacrifices in the name of the ideal and also the one for whom such a humanistic ideal is rendered. Sacrificial giving can never be separated from a continuous worship relationship with God in which our first sacrifice is sharing in Christ’s self-giving to the Father. Then and only then, as an overflow of that self-giving, may we participate in Christ’s service of others done, in the name of the Father and the Son, for them, not to them. There is no ethic of autonomous self-sacrifice, no simple human ideal of self-giving to another to fulfill. No other human being nor their circumstances can set the terms of our self-giving. Our self-giving must be moved, conditioned and controlled by God. There is no human sacrifice for the sake of other humans or humanity itself, since no human is divine — humanity is not God.

Perhaps it would be best if we removed the entire idea of sacrifice from Christian ethical thinking and restrict the notion of sacrifice to our exclusive relationship of worship with God. When speaking of our creaturely relations, it might be best to stick to the idea of self-giving for another. We would thus say that we sacrifice ourselves to God exclusively, but that sacrifice results in self-giving to others in Christ’s name, for the glory of God. Another way to say this is that all our relations with other human beings must be mediated by the lordship of Christ.

The point here is that all ethical activity must be done in and through Jesus Christ. Our Lord must stand between us and all others. He mediates not only our relationship to the Father and the Spirit, but also our relationships with other humans, and even with the natural environment. The New Testament way of indicating this is to say that everything we do, we do “in the name of the Lord,” or “in the Lord,” or “as unto the Lord,” or “for the glory of God.” We can love others with God’s kind of love only when it is defined, determined, moved and lived out with Christ regulating what we give to others and also what we are to receive from others.

The only way to come close to others, in a way that brings God’s kind of life, is to have Christ be a real, actual “insulator” between us and all others. That is why Jesus is and remains the Head of the Body of Christ, Lord over every member. No other member becomes that to us, even if others assist and help us remain in Christ, under his Lordship. All our relationships are to be mediated by Jesus Christ.

Beware a humanistic ideal of altruism

This critique of self-sacrifice (sacrificial giving) calls into question the ideal of altruism — doing good for another simply for the sake of doing good, with no thought for the self. This is sometimes called a disinterested love. But this humanistic ideal is no substitute for God’s agape love and our sharing in it through Jesus. Unfortunately, the two are often equated, especially by ethicists. But doing so is an error. The two must be carefully distinguished, which is done by seeing Christian love, service and self-giving, only as it is judged (sorted out) and directed by Jesus Christ.

Jesus’ love was not simply “un-selfish,” as altruists often claim. Such a claim is worldly. While Jesus’ love was not self-centered, it was not disinterested, expecting no benefit from it at all. No, Jesus’ love and self-giving was for the benefit of his Father, to point all to God and God’s glory and to bring about reconciliation to God so that his heavenly Father would be rightly worshiped by his creatures — those created through him (Christ), for him, and to him. It was for “the joy set before him [that] Jesus endured the cross” (Heb. 12:2). Jesus’ love was interested in the glory and worship of the Father — it was not altruistic in that it intended a particular outcome, namely, the benefit of those for whom he died that they might join him in worship of the Father in spirit and truth! A love that seeks the right and appropriate benefit is not a lesser love, contrary to what altruists assert.

As a human-centered (humanistic) ideal, self-sacrifice can become a horrific substitute for the kind of agape-sacrifice directed by God through Christ that leads to life now and forever. Promoted as the “highest” moral ideal (e.g., the only way that true love for God can be shown) needed to achieve a humanistic end (a utilitarian human-centered purpose, such as human survival, or the victory of a social/political ideology, a medical or technological advance, the advance of a religion, etc.), self-sacrifice can also be used to undermine a Christian theological ethic. It can be used to get us to depart from what the apostle Paul calls “the obedience of faith.” It can be used to pry people loose from living out of a worship relationship with the Triune God, who alone is worthy of our self-sacrifice, worthy of our complete surrender to him and his ways.

The way of a theological ethic is never self-centered. It is always theo-centric (Christo-centric). The obedience called for by this ethic results in sacrifice that is expressive of loyalty to the triune God, not loyalty (in the ultimate sense) to any created thing (including humans). Furthermore, a theological ethic always contributes to a theo-centric or Christo-centric witness that resists equating the two Great Commandments, then collapsing the first into the second, making the second, by default, the only commandment.

A truly Christian theological ethic both preserves and draws from the two Great Commands as taught and lived out by Jesus Christ, Son of the Father, Savior and Lord over all humanity.