Studies in Romans

| Site: | GCS Learning Center |

| Course: | Free Educational Resources for the Public from Grace Communion Seminary |

| Book: | Studies in Romans |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Wednesday, January 7, 2026, 7:34 AM |

Table of contents

- Romans

- Romans 1:1-7

- Romans 1:8-17

- Romans 1:18-32

- Romans 2

- Romans 3

- Romans 4:1-17

- Romans 4:13-25

- Romans 5:1-11

- Romans 5:12-19

- Romans 5:20-21

- Romans 6:1-11

- Romans 6:12-23

- Romans 7:1-14

- Romans 7:15-25

- Romans 8:1-11

- Romans 8:12-25

- Romans 8:26-39

- Romans 9:1-5

- Romans 9:6-33

- Romans 10:1-4

- Romans 10:5-15

- Romans 10:16-21

- Romans 11

- Romans 12:1-8

Romans

Paul's letter to the Romans

Romans 1:1-7

In the year A.D. 57, Paul was on his third missionary journey, getting ready to go back to Jerusalem with an offering from the churches in Greece. Although he knew he had enemies in Jerusalem, he was already thinking about his fourth missionary trip. He wanted to go to Spain, and the best travel route would take him through Rome. This could work out well, Paul thought. There are already Christians in Rome, and they might be willing to support my trip to Spain, just as the Antioch church supported my earlier missionary journeys and the Macedonian churches supported me while I was in southern Greece.

So Paul decided to write to the Roman Christians to let them know that he planned to come to Rome and then go to Spain — and that he would appreciate some support. However, Paul had a problem: the Roman Christians had heard some erroneous rumors about what Paul preached. To prevent misunderstanding, Paul explains what the gospel is, so they will know what they are being asked to support.

But that is only the first half of Romans. In the second half, Paul deals with some problems that existed in the Roman churches — especially the tension between Jewish Christians and Gentile Christians. Paul uses part of his letter to discuss Jew-Gentile relationships in God’s plan, and Christian conduct and love for others. He tries to give these Christians some doctrinal foundation for unity.

We do not know whether Paul made it to Spain, but his letter was a tremendous success in other ways. It has been valued throughout church history as the most doctrinally complete letter that Paul wrote. It is the letter that sparked the Reformation. It influenced Martin Luther and John Wesley and countless others. It provides the benchmark for all studies of Paul’s theology, and because of that, it is a cornerstone for understanding the doctrines of the early church.

Introduction to the gospel

Paul begins, as Greek letters normally did, by identifying himself: “Paul, a servant of Jesus Christ, called to be an apostle, set apart for the gospel of God…” (verse 1, New Revised Standard Version used in chapters 1-4). Paul identifies himself as a slave who has been commanded to spend his time on the gospel. He is sent by the master with the message of God.

Greek letters normally began by naming the sender, and then the recipients. But Paul is so focused on the gospel that, before he names the readers, he goes into a five-verse digression about the gospel. In effect, he puts his message at the top, before he even gets to the Dear so-and-so line. This makes it clear that his letter is about the gospel: “Which he promised beforehand through his prophets in the holy scriptures” (verse 2). Paul begins by linking the gospel to the Old Testament promises (as he also does in 1 Corinthians 15:3-4). This provides a point of stability for Gentile readers, and some reassurance for Jewish readers.

God’s message is “concerning his Son.” It is about the Son of God; the promises found in the Old Testament are fulfilled in Jesus Christ, “who was descended from David according to the flesh” (Romans 1:3). The gospel is again connected with the Old Testament past; Paul’s words will appeal to his Jewish readers and remind the Gentile readers of their Jewish roots.

The Son is a descendant of King David. However, by saying “according to the flesh,” Paul implies that something more than flesh is also involved. This person at the center of the gospel is not merely a human; he is also the Son of God in a way that other people are not.

Verse 4: “and was declared to be Son of God with power according to the spirit of holiness by resurrection from the dead, Jesus Christ our Lord.” Through the Holy Spirit, Jesus was powerfully demonstrated to be God’s Son by his resurrection from the dead. Jesus, although a human descendant of David, was shown to be more than human by his resurrection into glory.

But the gospel does not stop with Jesus. It also includes us: “through whom we have received grace and apostleship to bring about the obedience of faith among all the Gentiles for the sake of his name” (verse 5). Paul will say more about grace and obedience later in his letter. But he says here that “we” have not only received grace, but also apostleship. Paul is referring to his commission to take the gospel to the non-Jewish peoples, and by “we” he means the small number of people who were working with him in this special mission, such as Timothy. They have received the grace, the divine gift, of spreading the gospel.

He connects the gospel to the readers in verse 6: “including yourselves who are called to belong to Jesus Christ.” The gospel says that believers belong to Christ, and that is good news.

After this introductory description of the gospel, Paul gets back to the normal letter format by stating the recipients of the letter: “To all God’s beloved in Rome, who are called to be saints: Grace to you and peace from God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ” (verse 7). Paul does not greet “the church of God that is at Rome.” He does not speak of it as a unity. (Chapter 16 suggests that there were several house churches.) Nor does he write to any particular church leaders. Instead, perhaps because he is not sure how this letter will be delivered, he addresses it directly to the believers.

Romans 1:8-17

A prayer of thanks

Greek letters often included a prayer of thanksgiving to one of the gods, and Paul adapts this custom, thanking the true God: “First, I thank my God through Jesus Christ for all of you, because your faith is proclaimed throughout the world” (verse 8). This tells us that Paul prayed through Christ, and it also tells us that “all the world” doesn’t always mean the entire earth. In this case, it means the eastern Roman Empire. It was a figure of speech, not a geographical fact.

Paul gave God the credit for these people’s faith. He didn’t thank the people for believing — he thanked God, because God is the one who enables people to believe. Of our own, we would turn away. Even if we have only a small amount of faith, we need to thank God as the one who gives us that faith.

In verse 9, Paul calls God as his witness, to stress that he is telling the truth: “For God, whom I serve with my spirit by announcing the gospel of his Son, is my witness that without ceasing I remember you always in my prayers.” People today might say, “God knows that I pray for you all the time.” Paul adds that he serves God with his whole heart in preaching the gospel of his Son. He is keeping the gospel in the discussion, keeping his role as a servant in the context. These are his credentials; this is what his life is about. Paul’s authority does not rest on himself, but on his role as a servant of God. He is doing only what God wants, and the people therefore need to listen to what he says.

Paul’s plan to visit Rome

In verse 10 he adds something else: “asking that by God’s will I may somehow at last succeed in coming to you.” Paul is telling them that he hopes to visit them. This helps create a relationship between the author and the recipients.

“I am longing to see you,” he says in verse 11, “so that I may share with you some spiritual gift to strengthen you.” He wanted to help them — but he quickly adds, “or rather so that we may be mutually encouraged by each other’s faith, both yours and mine” (verse 12). Paul would be encouraged by them — at least, he hopes he would be! If I were there in person, he seems to be saying, we would both benefit. But since this is only a letter, the communication can go only one way, and this letter is Paul’s attempt to give them a spiritual gift to strengthen them.

Paul’s plan is not a spur-of-the-moment idea. “I want you to know, brothers and sisters, that I have often intended to come to you (but thus far have been prevented), in order that I may reap some harvest among you as I have among the rest of the Gentiles” (verse 13). Paul has often thought of going to Rome. Even when Paul lived in Jerusalem, he would have met people from Rome and would have heard stories about it. Paul has already gone as far as Greece — why not go farther, to the capital of the Empire, where many Jews had already gone? But so far, circumstances prevented Paul from doing it.

Why did Paul want to come? He wanted a harvest — he wanted more people to accept the gospel of Christ. Although many Jews lived in Rome, Paul focused on the Gentiles. They were his primary mission field, even if he went to the synagogues first. In the synagogues, Paul could find Gentiles who were prepared to receive the gospel.

An obligation to preach

“I am a debtor both to Greeks and to barbarians, both to the wise and to the foolish—hence my eagerness to proclaim the gospel to you also who are in Rome” (verses 14-15). Paul wanted to preach to everyone, and that’s why he wanted to preach in Rome, as well.

“For I am not ashamed of the gospel,” he says in verse 16. He has already used the word gospel twice and given a couple of descriptions of it. He has stressed that this is his calling in life, his duty before God. He is not ashamed of the gospel — and he doesn’t want the Romans to be ashamed of it, either. He describes it again in verse 16: “it is the power of God for salvation to everyone who has faith, to the Jew first and also to the Greek.” The gospel is the way that God saves people.

Technically, we are saved by Christ, by what he has done for us. But the gospel is the means by which we learn of that salvation and the way in which we receive it. The gospel is the power of salvation because it tells us about salvation. God uses the gospel to bring salvation to everyone who accepts the message, to everyone who trusts in Christ (since Christ is the center of the message, accepting the gospel means accepting Christ as well). Paul is not ashamed of the gospel because it is the message of eternal life. It is nothing to be ashamed of — it is something to be shared with everyone, both Jews and Gentiles.

Why is it a message of salvation? “For in it the righteousness of God is revealed through faith for faith; as it is written, ‘The one who is righteous will live by faith’” (verse 17, quoting Habakkuk 2:4). The gospel reveals the righteousness of God, and it reveals that his righteousness means more than strict justice — the gospel says that mercy is more important than justice. As Paul will explain, justice generally says that sin must be punished, but the gospel reveals that true righteousness involves mercy and grace. The fact that God’s righteousness must be revealed indicates that it is not the way that many people had assumed.

Is Paul saying that God’s righteousness is through faith? No, he is not talking about the way that God is righteous—he is talking about how his righteousness is revealed. We learn about it through faith, through believing the gospel. It is revealed through faith for faith, or literally, “from faith to faith.” Perhaps the best explanation of this phrase is that the Greek word for faith (pistis) can mean “faithfulness” as well as “belief.” When we come to believe in God’s righteousness, we respond by being faithful to him. We move from faith to faithfulness. Paul is not trying to explain it at this point; he is using a phrase that will make people want to continue reading to see how he will explain it.

Things to think about

- What does it mean to “belong” to Jesus Christ? (verse 6) In this relationship, what are my obligations, and what are his?

- How often do I thank God for the faith that others have? (verse 8)

- Am I willing to call God as my witness that I am telling the truth? (verse 9)

- When I visit a church, do I look for mutual encouragement? (verse 12)

- Do I have an obligation to share the gospel with other people? (verse 14)

- Am I ashamed of the gospel? (verse 16)

Photos by Ron Kelly

Author: Michael Morrison, 2003, 2014

Romans 1:18-32

Does God want to punish sinners, or to rescue them?

Paul introduces his letter to the Romans as a letter about the gospel, and he describes the gospel as “the power of God for salvation to everyone who has faith.” In the gospel, he says, God’s righteousness is revealed. The good news is that God, in his righteousness, is giving us salvation.

After stating his thesis, Paul explains the gospel in more detail, starting with our need for the gospel. Why do we need this message of salvation? Left on our own, we would be trying to live and form societies in wrong-headed ways. Paul explains that we were not going in a morally neutral direction — we were enemies of God, and we should therefore expect God to be angry at us. We need a message of good news so that we come to love God rather than be afraid of him.

The wrath of God

Paul explains the problem starting in verse 18: “For the wrath of God is revealed from heaven against all ungodliness and wickedness of those who by their wickedness suppress the truth.” God is angry at sin — and we should expect him to be. History books and newspapers report all sorts of crimes and atrocities that we should all be angry about. When one of our children hurts another, we should be angry. So God is right to be angry, and that’s why many people believe that God is going to punish all the people who do evil.

However, there is something odd about this. It is like a prison warden who is so angry at the prisoners that he sends his son into the prison to tell them how to escape, and he gives them the key to his own home so they will have a place to live. This is not what we normally expect from “wrath.” The gospel reveals that our concepts of God’s wrath are wrong.

Paul is turning religious assumptions upside down — he may begin with a concept like “wrath,” but he does not leave it there. The gospel reveals how Christ has turned things around. We cannot take verse 18 as Paul’s final statement on the matter, because it is not. It is merely the starting point in his explanation of the gospel. We need to see these verses as part of Paul’s strategy of explaining the gospel. He is starting with ideas that his readers probably agree with, but he explains that the gospel calls those assumptions into question.

People assume that God is angry at sinners because they sin even when they ought to know better. (In Paul’s day, it was generally people from a Jewish background who made this assumption; today it is generally Christian conservatives.) As Paul will soon explain, this would mean that God is angry at absolutely everybody. Instead, the gospel reveals a God who loves people even when they are his enemies, a God who sets the ungodly right, a God who rescues people from their addictions. He wants us to escape the punishment.

Verse 19 describes some of the common assumptions about why God would be angry at sinners: “For what can be known about God is plain to them, because God has shown it to them.” How did he make it plain? Verse 20: “Ever since the creation of the world his eternal power and divine nature, invisible though they are, have been understood and seen through the things he has made. So they are without excuse.”

Modern science tells us that the universe had a beginning. There was nothing, and there was suddenly something — a big bang, creating and filling the universe. This colossal explosion had a cause, a cause that existed before time did, a cause that was not part of the world the big bang created. Many people conclude that the cause was God. However, this gives only a rudimentary understanding of what God is. People might deduce that God is eternal and supernatural, but it says nothing about morality, and nothing about salvation. The gospel reveals something different: a God who came to his people in a form they did not expect. God’s most important characteristics are revealed not by creation, but by Christ.

God could make himself plain if he wanted to. He could be a pillar of fire, or he could write messages in the sky. He could make his existence unavoidable, but he chooses not to. He allows people to ignore him and reject him. We are not forced to quiver in front of an overwhelming power, so that our love can be freely given.

A bad trade

But many people reject God: “for though they knew God, they did not honor him as God or give thanks to him, but they became futile in their thinking, and their senseless minds were darkened” (verse 21). This was the common Jewish explanation of idolatry, as we see from other Jewish literature of this time period. Although people had an opportunity to know about God, they ignored him and did not show any appreciation. As a result, their thinking became futile — it did not produce any fruit. If we try to make sense out of life without God in the picture, we will never get the right answer.

“Claiming to be wise, they became fools; and they exchanged the glory of the immortal God for images resembling a mortal human being or birds or four-footed animals or reptiles” (verses 22-23). Most cultures claim to be wise, but if they think it is smart to reject truth and build on falsehood, then they are foolish. They are giving up something wonderful and ending up with snakes and fools to worship. Their gods can never be anything more than imitations.

Letting them do what they want

So what did God do? “Therefore God gave them up in the lusts of their hearts to impurity, to the degrading of their bodies among themselves” (verse 24). In the usual Jewish critique of paganism, God lets people suffer from the results of their erroneous ideas. They miss out on the wisdom and guidance of God. Jews commonly criticized the Gentile world about their sexual practices, and Paul uses that example. This is one way they “degrade” their bodies.

Paul repeats these thoughts in verses 25-26: “because they exchanged the truth about God for a lie and worshiped and served the creature rather than the Creator, who is blessed forever! Amen. For this reason God gave them up to degrading passions.” The people traded away truth and lived as if God did not exist. God was so “angry” that he let them do what they want.

Paul says: “Their women exchanged natural intercourse for unnatural, and in the same way also the men, giving up natural intercourse with women, were consumed with passion for one another. Men committed shameless acts with men and received in their own persons the due penalty for their error” (verses 26-27). Paul is not saying that God is going to punish them for their awful behavior. No, his emphasis is different. Paul is saying that God is already punishing them by letting them do these sexual sins. Paul is shifting the meaning of wrath and punishment.

The sins that people commit are results of their self-chosen alienation from God, and the results they get are the natural results of what they are doing. When we cut ourselves off from God, the things we want are often bad for us, and if God lets us do what we want, we end up doing things that are bad for us. Sexual sins are one example; Paul could have just as easily used greed as a different example, or dishonesty, or violence. Different problems appeal to different people, and if we just do what we want, we end up hurting ourselves as well as others. Verse 28 puts it like this: “Since they did not see fit to acknowledge God, God gave them up to a debased mind and to things that should not be done.”

Many examples

Paul gives many more examples in verses 29-31: “They were filled with every kind of wickedness, evil, covetousness, malice. Full of envy, murder, strife, deceit, craftiness, they are gossips, slanderers, God-haters, insolent, haughty, boastful, inventors of evil, rebellious toward parents, foolish, faithless, heartless, ruthless.” People do not want to live in a world of greed and envy, murder and deceit. They don’t want a world of depravity, arrogance and slander, but without God, that is where they end up.

Paul is echoing part of the standard Jewish view of the world, and he is building rapport with his Jewish readers. But he is setting them up, we might say — after presenting this judgmental worldview, he is going show that it condemns them just as much as it does the Gentiles. If God is going to punish sinners, then he will have to punish everyone. But as Paul will soon explain, this way of looking at the world is not right. The gospel has a different view of sin and judgment — it reveals the righteous mercy of God.

Jews traditionally believed that envy, murder, strife, and homosexuality are wrong. Paul does nothing to correct that view — we can see in his other letters that he agreed with them on that. But he disagreed with them on the consequences of that. The gospel reveals that God wants to rescue sinners, rather than destroy them. The fact that God forgives sins does not mean that God doesn’t care whether we do them. He wants us to avoid sin, but the gospel also announces that sin does not have the final word. Sin leads to death, but death does not have the final word.

Verse 32: “They know God’s decree, that those who practice such things deserve to die—yet they not only do them but even applaud others who practice them.” Maybe it seems harsh to say that a gossiper deserves to die, and that envious people deserve to die. But it is true: no one can say that the universe owes them eternal life. If they turn away from the Author and the Giver of life, then it is natural that they would cut themselves off from life.

However, there is something odd about this verse. Paul is saying that the people deserve to die. Paul seems to be agreeing with this judgment; he seems to be condemning people to death for their sins. But in the very next verse (chapter 2, verse 1), Paul criticizes people who pass judgment and condemn others! Is he criticizing himself? No, he is criticizing the religious worldview described in verse 32. The gospel reveals a God who gives salvation, and a God who is righteous in doing so. God’s righteous decree according to the gospel is life, not death.

The gospel is the power of salvation, and the revelation of God’s righteousness is the solution not only for the sins of paganism, but also the sin of being judgmental. God has acted to rescue people, to save them, to restore them to righteousness. As Paul will explain in later chapters, he has done it in Jesus Christ.

Things to think about

- In what way does creation inform me about God? (verse 20)

- Is it true that everyone has evidence of God? Why doesn’t God make himself more obvious?

- Are foolish desires a sin or a punishment? (verse 24)

- Which of the sins am I most likely to commit? (verses 30-31)

- Is God’s anger part of the gospel, or the setting in which the good news is revealed?

Author: Michael Morrison, 2003, 2012

Romans 2

Everyone needs the gospel

As part of Paul’s presentation of the gospel, he explains why it is needed. Paul begins with a typical Jewish criticism of Gentiles, which says that people ought to know God but are willingly ignorant and therefore deserve to die. But there is something wrong with this view, Paul says.

All are guilty

In Romans 2:1 Paul says, “Therefore you have no excuse, whoever you are, when you judge others; for in passing judgment on another you condemn yourself, because you, the judge, are doing the very same things.”

Does Paul mean that if you accuse someone of murder, you have committed murder? No; we need to see the context. In Romans 1:29-31, Paul had mentioned a variety of sins: “They were filled with every kind of wickedness, evil, covetousness, malice. Full of envy, murder, strife, deceit, craftiness, they are gossips, slanderers, God-haters, insolent, haughty, boastful, inventors of evil, rebellious toward parents, foolish, faithless, heartless, ruthless.”

In Romans 2:1, Paul is saying that whenever people pass judgment on someone else, when they say that those who do such things deserve to die, they are guilty of the same kind of thing — a sin. We are all guilty of something, so we should not judge other people. (Paul will say more about that in chapter 14.) If we condemn someone, we are saying that sinners deserve to be punished (1:32). But since we have sinned, we also deserve to suffer the unpleasant consequences.

Paul writes: “You say, ‘We know that God’s judgment on those who do such things is in accordance with truth’” (2:2). The Greek text does not have the words “you say.” Most translations present the verse as a statement of Paul; the NRSV says that this was part of the argument that others made. However, even if his opponents said this, Paul would probably agree with it, because God’s judgment is always in accordance with truth. The problem is that different people have different ideas about what that judgment is.

Verse 3 gives Paul’s response: “Do you imagine, whoever you are, that when you judge those who do such things and yet do them yourself, you will escape the judgment of God?” Everyone sins, so no one should be pointing fingers.

“Or do you despise the riches of his kindness and forbearance and patience? Do you not realize that God’s kindness is meant to lead you to repentance?” (2:4). If we judge others, we are showing contempt for God’s mercy — not only his mercy toward them, but also his mercy and patience toward us. God’s patience toward sinners should make us have a change of mind and be patient toward sinners, too.

Condemned by our works

In verse 5, Paul is still talking to the person who passes judgment on others: “But by your hard and impenitent heart you are storing up wrath for yourself on the day of wrath, when God’s righteous judgment will be revealed.” You might like to talk about the day of judgment, but if you persist in judging others, it will be worse for you on the day of judgment.

In the traditional view of judgment, God “will repay according to each one’s deeds: to those who by patiently doing good seek for glory and honor and immortality, he will give eternal life” (verses 6-7). If we take this out of context, it suggests that people can be saved on the basis of good works. But as Paul will soon argue, no one is good enough to earn eternal life through their works. This verse is part of the view that Paul is critiquing — he is not endorsing it. He is showing that this view of God’s judgment leads only to universal condemnation and despair. It is not good news.

“While for those who are self-seeking and who obey not the truth but wickedness, there will be wrath and fury. There will be anguish and distress for everyone who does evil, the Jew first and also the Greek” (verses 8-9). This is where Paul wants to go — applying this Jewish worldview to the Jews. If God is in the business of applying righteous punishment on all sinners, he will do it for the Jews as well as the Gentiles, because “God shows no partiality” (verse 11).

God will give “glory and honor and peace for everyone who does good, the Jew first and also the Greek” (verse 10). Paul will soon say that all have sinned; no one deserves glory, honor and eternal life.

In these verses Paul is describing a judgment of rewards that will never happen, because no one will ever qualify in this way. This is not a “straw man” that doesn’t exist, or a hypothetical situation that Paul made up just for the sake of argument — it was a view being taught by some people in the first century. Paul is showing that this religious belief is wrong; the gospel reveals that God envisions a much different outcome for humanity.

Equal treatment under the law

“All who have sinned apart from the law [Paul is referring to Gentiles here] will also perish apart from the law, and all who have sinned under the law [Jews] will be judged by the law” (verse 12). No matter who you are, if you sin, you will be condemned. This would be terrible news, if it weren’t for the gospel. The gospel is news we desperately need, and news that is very good — but it is especially good when we see how bad the alternative is.

Verse 13: “For it is not the hearers of the law who are righteous in God’s sight, but the doers of the law who will be justified.” Paul is not saying that people can actually be declared righteous by their obedience — he says that no one can be declared righteous in this way (3:20). Is he inconsistent, as some scholars claim? No, not when we realize that these words are not his own view, but the view he is arguing against. He is showing that this way does not work. The gospel reveals something; the word “reveals” indicates that it was different from the previous Jewish view.

How can God condemn Gentiles for breaking his law when they don’t know what it is? The traditional view said they had a chance, but they blew it (1:19). It said that if they would have heeded their conscience, they would have done what was right: “When Gentiles, who do not possess the law, do instinctively what the law requires, these, though not having the law, are a law to themselves. They show that what the law requires is written on their hearts, to which their own conscience also bears witness; and their conflicting thoughts will accuse or perhaps excuse them” (2:14-15).

As most people will admit, Gentiles keep some things required by the law. They teach that murder and theft are wrong. Gentiles have a conscience, and it sometimes says they did well — but sometimes it says that they did not. Even by their own standards, they fall short. That is how they can “sin apart from the law” (2:12). Even by their own standards, they fall short.

Paul tells us when this will happen in verse 16: “on the day when, according to my gospel, God, through Jesus Christ, will judge the secret thoughts of all.” Paul agrees with his opponents that there will be a day of judgment — but he introduces a big difference — this judgment will take place through Jesus Christ (cf. Acts 17:31).1

This changes everything. Paul will explain what a difference it makes a little later. But he has not yet finished showing the futility of the opposing view.

Advantages of the Jews

In verse 17, Paul begins to address some arguments that Jews might have:

But if you call yourself a Jew and rely on the law and boast of your relation to God and know his will and determine what is best because you are instructed in the law, and if you are sure that you are a guide to the blind, a light to those who are in darkness, a corrector of the foolish, a teacher of children, having in the law the embodiment of knowledge and truth… (verses 17-20)

If you have these advantages, Paul is saying, “you, then, that teach others, will you not teach yourself? While you preach against stealing, do you steal? You that forbid adultery, do you commit adultery? You that abhor idols, do you rob temples?” (verses 21-22). An individual reader might object: “I don’t steal and commit adultery.” But Paul is speaking of Jews as a group, and everyone knew that some Jews broke their own laws, even stealing from their own temple (Josephus, Antiquities 18.81-84).

Verse 23: “You that boast in the law, do you dishonor God by breaking the law?” If you have ever broken a law, you have dishonored God, and you are in the same category as thieves and adulterers — “sinner.” You know what you should do, and yet you fall short.

Paul uses Scripture to illustrate his point: “For, as it is written, ‘The name of God is blasphemed among the Gentiles because of you’” (verse 24). Ezekiel 36:22 says that the Jews had caused God’s name to be blasphemed. Jews are not immune to sin, and are not immune to judgment. The “judgment according to works” view has nothing good to say to them.

The true people of God

In verse 25, Paul comments on an advantage Jews thought they had: “Circumcision indeed is of value if you obey the law; but if you break the law, your circumcision has become uncircumcision.” As Paul will soon argue, everyone has broken the law — and circumcision doesn’t rescue anyone from the judgment.

“So, if those who are uncircumcised keep the requirements of the law, will not their uncircumcision be regarded as circumcision? Then those who are physically uncircumcised [the Gentiles] but keep the law will condemn you that have the written code and circumcision [Jews] but break the law” (verses 26-27). Some Jews taught that Gentiles could be saved if they obeyed the laws that applied to Gentiles, without being circumcised. So in such a case, the Gentile would be better off in the judgment than the Jew — a reversal of the picture that Jews usually drew.

“A person is not a Jew [that is, not one of God’s people] who is one outwardly, nor is true circumcision something external and physical. Rather, a person is a Jew who is one inwardly, and real circumcision is a matter of the heart—it is spiritual and not literal. Such a person receives praise not from others but from God” (verses 28-29). Just as Deuteronomy 30:6 said, circumcision should be in the heart, not just in the flesh. Just because someone is circumcised on the outside does not mean that he is truly part of the people of God who will be accepted on the day of judgment.

Paul is rattling the underpinnings of the traditional view — but he is not yet done. He is pulling his punches as part of his rhetorical strategy. He is saving his most powerful arguments for the next chapter — at this point he wants people to keep reading even if they sympathize with the opposing view. His opponents would have to agree in principle with what he says so far, though they might be uncomfortable with it. Paul wants them to keep reading, and we need to do that, too, if we want to see what the gospel reveals in contrast to the traditional view.

God is perfectly fair. Some Gentiles do what is right, and some Jews do what is wrong. But if both peoples are judged by what they do, then what advantage is there in being Jewish? That is precisely the question that Paul raises in the next chapter.

Things to think about

- What is my attitude toward sinners? Do I tend to condemn? (verse 1)

- How well do I appreciate God’s mercy toward me? (verse 4)

- Does my conscience ever defend me? (verse 15)

- How is judgment part of the gospel? (verse 16)

- If sin dishonors God (verse 23), what should my attitude be toward sin?

- What does it mean to have a Spirit-circumcised heart? (verse 29)

Endnote

1 Paul has shifted the basis of the judgment from works to thoughts. Although we all sin in our thoughts (even more often than in our works), Paul has shifted the focus away from exterior things, subtly preparing for his focus on faith. The thoughts by which we will be judged are actually our thoughts about Jesus Christ.

Author: Michael Morrison

Romans 3

From guilt to grace

In Romans 2, Paul explains that both Jews and Gentiles need the gospel — everyone needs salvation, or rescue from judgment. Although some Jews claimed to have an advantage in salvation, Paul explains that Jews are not immune to sin and judgment. Everyone is saved in the same way. So how do people become right with God? Paul explains it in chapter 3 — but first he has to answer some objections.

Any advantage for Jews?

Paul had preached in many cities, and he knew how people responded to his message. Jewish people often responded by saying: “We are God’s chosen people. We must have some sort of advantage in the judgment, but you are saying that our own law condemns us.” Paul asks the question that they do: “What advantage, then, is there in being a Jew, or what value is there in circumcision?” (3:1). What’s the point of being a Jew?

Paul answers in verse 2: “Much in every way! First of all, they have been entrusted with the very words of God.” The Jews have the Scriptures. That is an advantage, but there is a downside to it — those who sin under the law will be judged by the law (2:12). The law reveals requirements that the people do not meet.

So what’s the advantage? Paul will say more about that in chapter 9. But here in chapter 3 his goal is not to explain how special the Jews are, but to explain that they, just like everybody else, need to be saved through Jesus Christ. He’s not going to elaborate on their privileges until he has explained their need for salvation — they haven’t kept the law that they boast about.

So Paul asks: “What if some [Jews] were unfaithful? Will their unfaithfulness nullify God’s faithfulness?” (3:3). Will the fact that some Jews sinned cause God to back out of his promises?

“Not at all! Let God be true, and every human being a liar” (verse 4). God is always true to his word, and even though we are unfaithful, he is not. He won’t let our actions turn him into a liar. He created humans for a reason, and even if we all fall short of what he wants, his plan will succeed. God chose the Jews as his people, and they fell short, but God has a way to solve the problem — and the good news is that the rescue plan applies not only to Jews, but to everyone who falls short. God is more than faithful.

Paul then quotes a scripture about God being true: “As it is written: ‘So that you may be proved right when you speak and prevail when you judge’” (verse 4). This is quoted from Psalm 51:4, where David says that if God punishes him, it is because God is right. When God judges us guilty, it is because we are guilty. His covenant with Israel said that there would be unpleasant consequences for failure, and indeed, there had been many such times in Israel’s checkered history. God had done what he said he would.

Reason to sin?

Paul deals with another objection in verse 5: “But if our unrighteousness brings out God’s righteousness more clearly, what shall we say? That God is unjust in bringing his wrath on us? (I am using a human argument.)” Here is the argument: If we sin, we give God an opportunity to show that he is right. We are doing God a favor, so he shouldn’t punish us. It’s a silly argument, but Paul deals with it. Is God unjust? “Certainly not!” he says in verse 6. “If that were so, how could God judge the world?” God said he would judge the world, and he is right in doing so.

Paul paraphrases the argument a little in verse 7: “Someone might argue, ‘If my falsehood enhances God’s truthfulness and so increases his glory, why am I still condemned as a sinner?’” If my sin shows how good God is, why should he punish me? In verse 8 Paul gives another version of the argument: “Why not say — as some slanderously claim that we say — ‘Let us do evil that good may result’”? Paul stops dealing with the argument and repeats his conclusion by saying, “Their condemnation is just!” These arguments are wrong. When God judges us as sinners, he is right. The gospel does not give any permission to sin.

All have sinned

In verse 9 Paul returns to his discussion: “What shall we conclude then? Do we have any advantage?” Are we Jews better off than others? “Not at all! For we have already made the charge that Jews and Gentiles alike are all under the power of sin.” Jews have no advantage here, because we are all sinners — we are all under an evil spiritual force called sin. God does not play favorites, and he does not give salvation advantages to anyone.

In a rapid-fire conclusion, Paul quotes in verses 10 to 18 a series of scriptures to support his point that everyone is a sinner. These verses mention various body parts: mind, mouth, throat, tongue, lips, feet and eyes. The picture is that people are thoroughly evil:

- There is no one righteous, not even one [Ecclesiastes 7:20];

- There is no one who understands; there is no one who seeks God.

- All have turned away, they have together become worthless;

- There is no one who does good, not even one [Psalms 14:1-3; 53:1-3].

- Their throats are open graves; their tongues practice deceit [Psalm 5:9].

- The poison of vipers is on their lips [Psalm 140:3].

- Their mouths are full of cursing and bitterness [Psalm 10:7].

- Their feet are swift to shed blood; ruin and misery mark their ways, and The way of peace they do not know [Isaiah 59:7-8].

- There is no fear of God before their eyes [Psalm 36:1].

Those scriptures are true about Gentiles, some Jews might say, but not about us. So Paul answers them in verse 19: “Whatever the law says, it says to those who are under the law.” These Scriptures (the law in a larger sense) apply to people who are under the law — the Jews. They are sinners. Gentiles are, too, but Paul doesn’t have to prove that — his audience already believed that.

Why do the scriptures apply to the Jews? “So that every mouth may be silenced and the whole world held accountable to God.” Humanity will stand before the judgment seat of God, and the result is described in verse 20: “Therefore no one will be declared righteous in his sight by the works of the law.” By the standard of the law, we all fall short.

What does the law do instead? Paul says: “Rather, through the law we become conscious of our sin.” The law sets a standard of righteousness, but because we sin, the law can never tell us that we are righteous. It tells us that we are sinners. According to the law, we are guilty.

A righteousness from God

Paul introduces the good news in verse 21 with the important words “But now.” He’s making a contrast: We can’t be declared righteous by the law, but there is good news—there is a way that we can be declared righteous: “But now apart from the law the righteousness of God has been made known, to which the Law and the Prophets testify.” Here Paul gets back to what he announced in Romans 1:17, that the gospel reveals God’s righteousness.

Since we are sinners, we cannot be declared righteous by observing the law. It must be through some other means. God will declare us righteous in a way other than through the law. And although the law does not make us righteous, it does give evidence about another means of righteousness: “This righteousness is given through faith in Jesus Christ1 to all who believe. There is no difference between Jew and Gentile” (3:22). This righteousness is a gift! We do not deserve it, but God gives us the status of being counted as righteous. He gives this to all who believe in the gospel of Jesus Christ. Because Jesus was faithful, we can be given the status of being righteous.

This pathway to righteousness gives no advantage to the Jew — all are counted righteous in the same way. There is no difference, Paul says, “for all have sinned” — both Jews and Gentiles have sinned — “and [everyone] falls short of the glory of God.” When our works are judged by the law, we all fall short, and no one deserves the salvation that God has designed for us. But our weakness will not stop God’s plan!

“All are justified [declared righteous] freely by his grace through the redemption that came by Christ Jesus” (verse 24). Because of what Jesus did, we can be made right, and it is done as a gift, by God’s grace. We are not made sinless and perfect, but in the courtroom of God, we are declared righteous instead of guilty, we are accounted as acceptable to God and as faithful to the covenant. Whether we feel forgiven or not, we are forgiven because Christ paid our debt in full.

What permits God to change the verdict? Paul uses a variety of metaphors or word-pictures to explain this. Jesus has paid a price to rescue us from slavery. He has bought us back; that is what “redemption” means. That is one way to look at it, in financial terms. Courtroom terms have also been used, and in the next verse Paul uses words from Jewish worship:

“God presented Christ as a sacrifice of atonement, through the shedding of his blood — to be received by faith.” God himself provided the payment, the sacrifice that sets aside our sin. For “sacrifice of atonement,” Paul uses the Greek word hilasterion, the word used for the mercy seat on top of the ark of the covenant, a place where Israel’s sins were atoned every year on the Day of Atonement.2

Because of his love and mercy, God provided Jesus as the means by which we can be set “at one” with him. That atonement is received by us through faith; we believe that Jesus’ death did something that allows us to be saved. Paul is talking about three aspects of salvation: The cause of our salvation is what Jesus did; the means by which it is offered to us is grace; and the way we receive it is faith.

God provided Jesus as an atonement, verse 25 says, “to demonstrate his righteousness” — to show that he is faithful to his promises — “because in his forbearance he had left the sins committed beforehand unpunished.” Normally, a judge who let criminals go free would be called unjust (Exodus 23:7; Deuteronomy 25:1). Is God doing that? No, this verse says that God is not unjust when he justifies the wicked because he has provided Jesus as a means of atonement.

He is within his legal rights, to use a human analogy, in letting people escape because their sins have already been compensated for in the death of Jesus Christ. Even for people who lived before Christ, the payment was as good as done. In one sense, that applies to everyone, to the whole world: sins are paid for even before people become aware of it and believe it. But only those who believe it can be freed from the fear of punishment.

Romans 3:26 says that God “did it to demonstrate his righteousness at the present time, so as to be just and the one who justifies those who have faith in Jesus.” In the sacrifice of Jesus Christ, God demonstrates that he is just even when he declares sinners to be just. He has “earned the right” to count us as righteous.

All are equal

“Where, then, is boasting?” Paul asks in verse 27. Can the Jew boast about advantages over Gentiles? When it comes to salvation, there’s nothing to boast about. We can’t even boast about faith. Faith does not make us better than other people — we are only receiving what God gives. We can’t take credit for that, or brag about it.

Boasting “is excluded. Because of what law? The law that requires works? No, because of the law that requires faith” (verse 27). If people were saved by keeping the law, then they could brag about how well they did. But when salvation is by grace and faith, no one can boast. Paul is making two points that reinforce each other: That no one can boast, and that righteousness is by grace rather than by the law or by works. It takes faith because we don’t have the physical evidence to prove that we are righteous—all we have is the promise of God in Jesus Christ.

In verse 28, he says it again: “For we maintain that a person is justified by faith apart from the works of the law.” Being counted right with God on the day of judgment can never be on the basis of the law. The law can’t do anything except point out where we fall short. If we are going to be accepted by God, it will not be on the basis of the law, but because of the righteousness of Jesus Christ.

“Is God the God of Jews only?” Paul asks. “Is he not the God of Gentiles too? Yes, of Gentiles too, since there is only one God” (verses 29-30). God is not the exclusive possession of the Jews. According to the gospel, God “will justify the circumcised by faith and the uncircumcised through that same faith.” He makes Jews righteous in the same way that he makes Gentiles righteous, and that is through faith, not through the law.

“Do we…nullify the law by this faith?” Of course not, Paul says in verse 31. “Rather, we uphold the law.” The gospel does not contradict the law, but it puts law in its proper place. The law was never designed as a means of salvation. But the salvation it hinted at is now available to all through Jesus Christ. Paul does not yet say how we “uphold the law.” For that, we will have to continue reading in his letter.

Things to think about

- Did the Jews, by having the Scriptures, have an advantage in salvation? (verse 2)

- Does our sin give God an opportunity to be more gracious? (verse 7)

- Are people really worthless, no one good for anything? (verses 10-12)

- If the law can’t declare us righteous, what is it good for? (verse 20)

- In verses 22, 24, 26 and 28, Paul tells us how we are justified or declared righteous. What does he stress by repetition?

- How does Jesus’ sacrifice demonstrate God’s justice? (verse 25)

- How does Paul want us to respond to this chapter?

Endnotes

1 The NRSV footnote on verse 22 says the Greek words can also mean “through the faith of Jesus Christ.” It is theologically correct that we are saved through the faithfulness of Jesus, through his obedience (see Romans 5:19). The only reason that we can have faith in him is because he was completely faithful. But in order for us to experience the results of his faithfulness, we also need faith in him, in what he did. We do not need to resolve the question about the best translation of Romans 3:22 at this point. It is possible that Paul’s original readers were not completely sure of what Paul meant with this phrase. Paul may have given them a phrase that required them to continue reading to get the whole picture.

2 The cover of the ark was the location of atonement, but it was not a place of sacrifice. It may therefore be better to translate hilasterion as “place of atonement,” as done in the NRSV footnote. Some translations use the word “propitiation,” a word Greeks used to describe someone appeasing the anger of the gods. But this would mean that God supplied something to appease his own anger, which implies that he didn’t really want to be angry, but had to perform a ritual so he could get his original wish. This puts God into a convoluted position; it is simpler to say that God provided a means of atonement, because his original wish was atonement, being in fellowship with the humans he had created.

Author: Michael Morrison, 2003, 2012

Romans 4:1-17

The example of Abraham

In the last section of Romans 3, Paul declares that the gospel of salvation announces a righteousness from God, a righteousness that is given “through faith in Jesus Christ for all who believe” (3:22). Believers are justified or saved by faith, not by observing the law (3:28).

But some people object: Paul, are you saying that the law is wrong? Paul answers: “By no means! On the contrary, we uphold the law” (3:31). Paul began this section by saying the Law and the Prophets testify to this gift of righteousness (3:21). He began the entire letter by saying that his gospel had been promised in the Scriptures (1:2).

The law was designed to lead people to the gospel, and the gospel does not nullify the law in the same way that the Messiah does not nullify the prophecies that predicted his coming. Rather, he fulfills them. Similarly, the gospel fulfills the law, brings it to completion, and accomplishes what the law could only point at.

Abraham’s faith

Paul illustrates this with an example from the Old Testament. The patriarch Abraham is a great example of what Paul is saying — that salvation is given on the basis of faith, not through the law. In Romans 4, Paul elaborates on the meaning of both justification and faith. He asks in verse 1, “What then are we to say was gained by Abraham, our ancestor according to the flesh?”

He sharpens the focus of the question by saying, “For if Abraham was justified by works, he has something to boast about, but not before God” (verse 2). If Abraham was considered righteous because of his works, he would have something he could brag about, even though it would not put him anywhere near to God.

Paul has already said that boasting is excluded (3:27). He is contrasting two approaches to righteousness — one based on what people do and can take credit for, as opposed to one that depends on faith, which they cannot brag about but merely accept with thanks. What kind of righteousness did Abraham have?

Paul finds an answer in the Law: “For what does the scripture say? ‘Abraham believed God, and it was reckoned to him as righteousness’” (4:3, quoting from Genesis 15:6). Abraham’s belief was counted as righteousness. The patriarch, representing the entire nation (and even the world), was declared to be righteous not on the basis of what he did, but on the basis of believing God’s promise.

Justifying the wicked

Paul then begins to reason what this means. He builds the contrast between works and faith: “Now to one who works, wages are not reckoned as a gift but as something due” (verse 4). Abraham was given his status — if he had earned it through good works, then God would not have to credit his faith as righteousness. Some Jews thought that Abraham was perfect in his behavior, and God was obligated to count him righteous, but Paul is saying that, according to the Scriptures, Abraham had to be counted righteous on the basis of faith.

Paul then says, “But to one who without works trusts him who justifies the ungodly, such faith is reckoned as righteousness” (verse 5). Paul is increasing the contrast — he is not talking about someone who has both works and faith, but someone who believes but does not have good works. Of course, works normally follow faith. But at this point in the story, Abraham had only faith, and no works. He trusted God, and his faith was credited as righteousness.

Paul increases the contrast again by saying that God justifies the wicked. He is using a strong word, one not normally associated with Abraham. But Jews had only two categories of people: the righteous and the wicked. And if God had to intervene in order for Abraham to be counted as righteous, then that meant that he was not righteous beforehand, and he had been in the category of the wicked.

God does not need to rescue the righteous. He saves the wicked; there is no point in saving people who aren’t in any danger. Abraham was a sinner, but because of his faith, he is now counted as righteous.

Evidence from the Psalms

Paul will return to the example of Abraham in a few verses. But at this point he gives more evidence from the Old Testament that God can count the wicked as righteous. Paul uses Psalm 32, written by David, another highly respected patriarch of the Jewish people: “So also David speaks of the blessedness of those to whom God reckons righteousness apart from works: ‘Blessed are those whose iniquities are forgiven, and whose sins are covered; blessed is the one against whom the Lord will not reckon sin’” (4:6-8).

David talks about someone who had sins, who would have to be counted wicked if judged by works, but who had all their sins forgiven. David didn’t mention faith here, but he is talking about a person to whom God credits righteousness apart from works. There is a way to be right with God that doesn’t depend on behavior. The sins are not counted against us.

For Jews only?

Paul then returns to the example of Abraham, asking, “Is this blessedness, then, pronounced only on the circumcised, or also on the uncircumcised?” (verse 9). Is the blessing of forgiveness available only to Jews, or also to Gentiles? Can Gentiles be counted among the righteous? “We say,” he reminds them, “‘Faith was reckoned to Abraham as righteousness.’ How then was it reckoned to him? Was it before or after he had been circumcised? It was not after, but before he was circumcised” (verses 9-10).

Abraham was circumcised in Genesis 17. So in Genesis 15 (which is 14 years earlier), when his faith was counted as righteousness, he was not circumcised. Not only was Abraham credited with being righteous apart from works in general, he was counted as righteous apart from Jewish works in particular.

Therefore, a person doesn’t have to become Jewish in order to be saved. They don’t have to become circumcised, or keep the laws that distinguished Jews from Gentiles, because Abraham was a Gentile when he was counted as righteous. Abraham shows that God doesn’t mind calling sinners righteous, and he doesn’t require circumcision, or the laws of Moses.

Abraham “received the sign of circumcision as a seal of the righteousness that he had by faith while he was still uncircumcised” (verse 11). Abraham became circumcised 14 years later, but that doesn’t prove that we also need to become circumcised after we come to faith. Circumcision was simply a sign of the righteousness that he already had. That didn’t add anything to his righteousness and didn’t change his category.

Paul concludes, “The purpose was to make him the ancestor of all who believe without being circumcised and who thus have righteousness reckoned to them.” Abraham is the father of all the Gentiles who believe. He set the precedent for an uncircumcised person being counted as righteous.

“And likewise [he is] the ancestor of the circumcised who are not only circumcised but who also follow the example of the faith that our ancestor Abraham had before he was circumcised” (verse 12). As Paul has already argued, a person is not a Jew if he is only one outwardly (2:28). To truly belong to the people of God, a person must be changed in the heart, not necessarily in the flesh. If Jewish people want to be counted among the people of God, they need faith — the same kind of faith that Abraham had before he was circumcised.

The basis of salvation is faith, not flesh. Gentiles don’t need to copy Jews in order to be saved. Instead, Jews need to copy a Gentile — that is, Abraham, before he was circumcised. We all need to copy the Gentile named Abraham.

Faith, not law

Paul now brings the word law back into the discussion: “For the promise that he would inherit the world did not come to Abraham or to his descendants through the law but through the righteousness of faith” (verse 13). The law of Moses wasn’t even around in the days of Abraham. Paul is saying that the promise wasn’t given by law at all.

God didn’t say, If you do this or that, I will bless you. No, he simply said he would bless him. It was an unconditional promise: “Abraham, you are going to have descendants enough to fill the earth, and the whole world is going to be blessed through you.” Abraham believed that promise, and that is why he was counted as righteous. It was not on the basis of a law.

Because, Paul reasons, “If it is the adherents of the law who are to be the heirs, faith is null” (verse 14). It’s either faith or law — it cannot be both. If we are saved by our works, then we are looking to our works, not trusting in God. If Abraham had earned this blessing by keeping a law, then there would be no point in mentioning his faith.

But even more seriously, Paul says that if salvation is by law, then the promise would be “void. For the law brings wrath” (verses 14-15). The promise would do us no good because we all fall short of what the law requires. We are sinners, and all the law can do for us is bring wrath and punishment. It cannot deliver the promises, because by its criteria, we fall short.

If salvation is by the law, then we have no hope. The good news, however, is that “where there is no law, neither is there violation” (verse 15). If salvation is not on the basis of the law, then we cannot disqualify ourselves through our transgressions. Since the law is not part of the method by which we are saved, our sins are not part of the picture, either. They don’t take away what God has given to us by a promise (see 8:1).

By faith

“For this reason,” Paul says in Romans 4:16, “it depends on faith, in order that the promise may rest on grace and be guaranteed to all his descendants, not only to the adherents of the law but also to those who share the faith of Abraham” (verse 16). The promise given to Abraham was for uncountable descendants, and we can share in Abraham’s promise by being one of his descendants, through a spiritual union with Jesus, who descended from Abraham.

The promise of salvation comes to us by faith, by grace, not by works, and it is consequently guaranteed. We don’t have to be afraid that we will lose our salvation through some sin that we have trouble getting rid of. Grace doesn’t keep count of works, either good or bad. In this way, the promise goes not only to the Jews, but to all people. We just have to trust Jesus.

Abraham is “the father of all of us,” Paul concludes, and he follows it up with a confirming quote from the Torah: “As it is written: ‘I have made you the father of many nations’” (verse 17, quoting Genesis 17:5 and using the common word for Gentiles). Abraham is the father not just of the Jewish nation, but of many other nations. Gentiles are also his descendants, and they do not have to become Jewish in order to be counted.

Paul writes about “the God in whom he believed, who gives life to the dead and calls into existence the things that do not exist” (verse 17). Why does Paul bring this up? Perhaps he is thinking of the spiritually dead — Gentiles and unbelieving Jews. God can rescue them, and he can take people who were alienated, and make them his people. He can take people who are wicked and call them righteous. He does not want them to remain wicked, but that is where they start.

Romans 4:13-25

Faith, not law

Paul now brings the word law back into the discussion: “For the promise that he would inherit the world did not come to Abraham or to his descendants through the law but through the righteousness of faith” (verse 13). The law of Moses wasn’t even around in the days of Abraham. Paul is saying that the promise wasn’t given by law at all.

God didn’t say, If you do this or that, I will bless you. No, he simply said he would bless him. It was an unconditional promise: “Abraham, you are going to have descendants enough to fill the earth, and the whole world is going to be blessed through you.” Abraham believed that promise, and that is why he was counted as righteous. It was not on the basis of a law.

Because, Paul reasons, “If it is the adherents of the law who are to be the heirs, faith is null” (verse 14). It’s either faith or law — it cannot be both. If we are saved by our works, then we are looking to our works, not trusting in God. If Abraham had earned this blessing by keeping a law, then there would be no point in mentioning his faith.

But even more seriously, Paul says that if salvation is by law, then the promise would be “void. For the law brings wrath” (verses 14-15). The promise would do us no good because we all fall short of what the law requires. We are sinners, and all the law can do for us is bring wrath and punishment. It cannot deliver the promises, because by its criteria, we fall short.

If salvation is by the law, then we have no hope. The good news, however, is that “where there is no law, neither is there violation” (verse 15). If salvation is not on the basis of the law, then we cannot disqualify ourselves through our transgressions. Since the law is not part of the method by which we are saved, our sins are not part of the picture, either. They don’t take away what God has given to us by a promise (see 8:1).

By faith

“For this reason,” Paul says in Romans 4:16, “it depends on faith, in order that the promise may rest on grace and be guaranteed to all his descendants, not only to the adherents of the law but also to those who share the faith of Abraham” (verse 16). The promise given to Abraham was for uncountable descendants, and we can share in Abraham’s promise by being one of his descendants, through a spiritual union with Jesus, who descended from Abraham.

The promise of salvation comes to us by faith, by grace, not by works, and it is consequently guaranteed. We don’t have to be afraid that we will lose our salvation through some sin that we have trouble getting rid of. Grace doesn’t keep count of works, either good or bad. In this way, the promise goes not only to the Jews, but to all people. We just have to trust Jesus.

Abraham is “the father of all of us,” Paul concludes, and he follows it up with a confirming quote from the Torah: “As it is written: ‘I have made you the father of many nations’” (verse 17, quoting Genesis 17:5 and using the common word for Gentiles). Abraham is the father not just of the Jewish nation, but of many other nations. Gentiles are also his descendants, and they do not have to become Jewish in order to be counted.

Paul writes about “the God in whom he believed, who gives life to the dead and calls into existence the things that do not exist” (verse 17). Why does Paul bring this up? Perhaps he is thinking of the spiritually dead — Gentiles and unbelieving Jews. God can rescue them, and he can take people who were alienated, and make them his people. He can take people who are wicked and call them righteous. He does not want them to remain wicked, but that is where they start.

Abraham’s faith

Paul concludes with a summary of the story of Abraham. His audience knew the story well, but Paul emphasizes certain points to reinforce what he has been saying:

Hoping against hope, he believed that he would become “the father of many nations,” according to what was said, “So numerous shall your descendants be.” [Genesis 15:5]. He did not weaken in faith when he considered his own body, which was already as good as dead (for he was about a hundred years old), or when he considered the barrenness of Sarah’s womb. No distrust made him waver concerning the promise of God, but he grew strong in his faith as he gave glory to God, being fully convinced that God was able to do what he had promised. (verses 18-21)

In his own flesh, Abraham didn’t have any reason to hope, but he had faith in what God had promised, and his faith was a witness to how great God is. Abraham knew that the promise was physically impossible, but he trusted in God’s power and faithfulness rather than in his own abilities.

In our salvation, too, we have no hope according to the flesh, no hope according to our works, but we can trust in the promise of God, given to Abraham and extended through Jesus Christ to all who believe in him. We should not be discouraged by our human inability to be righteous, but we should trust in the promise of God to count us righteous on the basis of faith. Paul reminds us that because Abraham trusted in God, “Therefore his faith ‘was reckoned to him as righteousness’” (Genesis 15:5). We don’t even believe as well as we ought to, but Jesus takes care of that for us, too. He is our judge, and that changes everything.

As his final point, Paul reasons that “the words ‘it was reckoned to him,’ were written not for his sake alone, but for ours also” (verses 23-24). Those words were not written for Abraham at all, for they were written long after he died. They were written for us, so that we will also have faith. We are the ones to whom righteousness will be reckoned: “to us who believe in him who raised Jesus our Lord from the dead” (verse 24).

No matter whether we are Gentile or Jewish, we will be counted as righteous, as God’s people, if we trust in God. What he did for Jesus, he will do for us: raise us from the dead. He has done it before, and he will do it again.

Paul concludes the chapter with a brief restatement of his gospel message: Jesus Christ “was handed over to death for our trespasses and was raised for our justification” (verse 25). The deed has been done; the promise has been given. He died for our sins, and he now lives to ensure that we are accepted by God. We need to accept his gift — the gift of righteousness — given to those who believe in Jesus Christ. If God can raise the dead, he can save anyone!

Things to think about

- If God saves the wicked (verse 5), does that allow me to be wicked? Why would I want to be wicked?

- What is the seal or evidence of my righteousness? (verse 11)

- Does the law have any role in my salvation? (verse 14)

- If salvation is guaranteed (verse 16), can I refuse it or lose it?

- Am I discouraged by my own weaknesses? (verse 19)

- What gives me evidence that God will save me? (verse 24)

Author: Michael Morrison, 2003, 2012

Romans 5:1-11

In the first four chapters of Romans, Paul announced that the gospel is a message about the righteousness of God being given to people because of Jesus Christ. First, Paul described the problem: Everyone deserves to die because we all fall short of what God wants.

Then Paul described the solution: The gift of God is eternal life in Christ Jesus our Lord. It is a gift, not a result of us keeping laws. In chapter 4, Paul proved this with the example of Abraham, who was declared righteous by God on the basis of faith before the laws were given. Salvation is by grace and faith, not by law or works.

Faith, hope and love

In chapter 5, Paul explains a little more — and in the process, he says a few things that have caused questions for centuries. We will discuss these and notice the main point that Paul makes. He says in verse 1, “Therefore, since we have been justified through faith” — that’s the main point of chapters 3 and 4 — “we have peace with God through our Lord Jesus Christ” (NIV used in chapters 5-16). The problem between us and God has been fixed.

Before, we were sinners, enemies of God, and unless something was done, we deserved to be punished. But since we were powerless to do anything about it, God took the initiative — he sent his Son to bring us peace. In legal terms, we have been declared righteous, and in relationship terms, we are given peace instead of hostility.

It is through Jesus, Paul says in verse 2, that “we have gained access by faith into this grace in which we now stand. And we boast in the hope of the glory of God.” We enter grace, or forgiveness, by faith in what Christ did. When Paul says that we stand in grace, he implies that we can remain in this state. Because of God’s grace, based on what Christ did in the past, we rejoice in the hope that this gives us for the future—confidence that we will share in the glory of God. This hope is not just a wishful thought—it is guaranteed by what God has done for us.

This has practical results in our lives: “Not only so, but we also glory in our sufferings, because we know that suffering produces perseverance; perseverance, character; and character, hope” (verses 3-4). We rejoice not only in hoping for future glory, but we rejoice now, even when things are not going well for us.

We may not rejoice because of our sufferings, but we can rejoice in them. Trials and difficulties help us grow in determination to endure, and in our character, our consistency in doing the right thing even in difficult circumstances. If we stay on the right path, we can be confident that we will get to the goal. Our source of confidence is not in ourselves, but in what Jesus is doing in us.

Paul says more about hope in verse 5: “Hope does not put us to shame, because God’s love has been poured out into our hearts through the Holy Spirit, who has been given to us.” We do not hope in vain, because even in this life we have benefits in Christ, such as the love that God puts into us. Our ability to love is increased because God begins to put his own characteristics into our hearts, and that includes love.

By doing this, God lets us know that he loves us, and he helps us love others, through the Holy Spirit living in us. God gives us something of himself, so we are changed to be more like he is. Through faith, God gives us hope and love. He is changing our outlook on life and the way we live.

Saved by his love

Paul then tells us what he means about God’s love: “At just the right time, when we were still powerless, Christ died for the ungodly” (verse 6). Who are the “ungodly”? We are! No matter how ungodly we have been, Christ is able to save us. He didn’t wait until we repented; he did not wait until we deserved it. No — he died for us while we were powerless. He helped us when we were helpless.

“Very rarely will anyone die for a righteous person, though for a good person someone might possibly dare to die” (verse 7). It’s not likely that we can die for someone else, though some people do risk their lives to save others. This rare situation provides a contrast to Christ: “But God demonstrates his own love for us in this: While we were still sinners, Christ died for us” (verse 8). He had to do it while we were sinners, because sin is what we had to be rescued from. So God took the initiative, sending Christ to die for us, and this demonstrates God’s love. He is good to us even when we are rebels; he gives generously even when we deserve nothing.

The action of Christ demonstrates the love of God, because Christ is God. They have the same love because they are one. When we have trials, we can look to Jesus as evidence that God loves us. His willingness to die for us should reassure us that God wants to help us, even at great cost to himself.

Paul draws a conclusion in verse 9: “Since we have now been justified by his blood, how much more shall we be saved from God’s wrath through him!” Because of what Jesus did in the past, we are now forgiven, and on the day of judgment we will will not be condemned—we will be counted among the righteous.

Paul explains his reasoning in verse 10: “For if, while we were God’s enemies, we were reconciled to him through the death of his Son, how much more, having been reconciled, shall we be saved through his life!” If God did this much for us when we were enemies, we can be sure that he will accept us now that Jesus has reconciled us, and he now lives for us.

Not only is this so, but we also boast in God through our Lord Jesus Christ, through whom we have now received reconciliation (verse 11). We rejoice in the hope of the glory of God and we rejoice in our sufferings, but we especially rejoice in being reconciled to God, because he is better than all his blessings put together. We will spend eternity with a good relationship with God.

Romans 5:12-19

Christ and Adam

In the next section of this chapter, Paul makes a contrast between Adam and Christ. His question is, How can one person bring salvation to the whole world? Paul shows that in God’s way of doing things, one person can indeed have that much effect on others. “Therefore,” he begins in verse 12, and he follows it with a comparison — “just as such and such…” — but he does not finish the thought until verse 18. He first has to tell us how he reached his conclusion.

So verse 12 introduces to us what he wants to say: “Therefore, just as sin entered the world through one man, and death through sin, and in this way death came to all people, because all sinned…..” He’s going to say that just as sin entered the world through one person, salvation also entered the world through one person, and just as Adam brought death to all who followed him, Christ brought life to all who follow him.

Death is a consequence of sin (Genesis 2:17). Paul may be thinking of physical death, or of spiritual death. Either way, Christ brings life after death, life that reverses the results of sin.

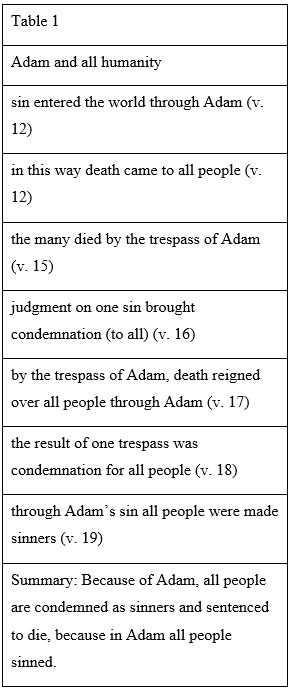

This section of Romans 5 has been important in Christian theology because it teaches that all people are counted as sinful because Adam sinned. This is the doctrine of original sin. These verses say that Adam’s sin affected all humanity (for a summary, see Table 1). But Paul’s main point is the contrast between Adam and Christ (Table 2). In verse 12, Paul says that everyone sinned — that’s in the past tense. We all sinned when Adam sinned, because his sin counted for all his descendants. Because of what he did, we all sin and die. And since what Adam did affected everyone, it should be no surprise that what Christ (our Creator) did could also affect everyone.

Christ and Adam

Christ and Adam

In verse 13 Paul explains how he reached his conclusion: “Sin was in the world before the law was given, but sin is not charged against anyone’s account where there is no law. Nevertheless, sin reigned from the time of Adam to the time of Moses, even over those who did not sin by breaking a command, as did Adam, who is a pattern of the one to come” (verses 13-14).

People before Moses sinned, breaking unwritten laws. But Paul is connecting their sin with Adam. The people were counted as sinners not only because of their own sins, but also because of what Adam did. Adam was a pattern of a future man — Jesus. There is more contrast than similarity, as Table 2 shows.

“But the gift [of God] is not like the trespass. For if the many died by the trespass of the one man, how much more did God’s grace and the gift that came by the grace of the one man, Jesus Christ, overflow to the many!” (verse 15). The grace of Christ is a total reversal of the sin of Adam. Everyone died because of Adam’s transgression, but because of Christ, everyone can live. Everyone was judged guilty because of Adam’s sin; everyone can be judged righteous through faith in Christ.

| verse | Table 2 | |

| 12 | Adam brought sin and death to all humanity | |

| 15 | his sin caused the death of all his descendants | because of Christ, grace overflows to all |

| 16 | judgment on Adam’s sin condemned everyone | grace brought acquittal to all, even after many sins |

| 17 | death reigned over all because of Adam’s sin | with grace, people reign in life through Christ |

| 18 | his sin condemned all people to death | one act of obedience brings life to all people |

| 19 | one sin made many sinners | Christ’s obedience will make many righteous |

“Nor can the gift of God be compared with the result of one man’s sin: The judgment followed one sin and brought condemnation, but the gift followed many trespasses and brought justification” (verse 16). The contrast is partly in the numbers: one sin produced condemnation for all people, but even after a tidal wave of sins, one man brought justification for the same people. Judgment said we deserved death, but grace said we were acceptable to God.